I have never been an employee of the month. This is probably because I’ve rarely worked the sort of job that had such a perk—usually service sector, usually with enough employees that making them compete against each other is a viable stratagem, almost always involving the sort of unpleasant drudgery that such corporate boosterism seeks to mitigate or disguise. The place of honor on the business wall given to the current top performer, often near numerous framed photographs of former honorees—a sort of reliquary of Employees of the Past—meant to serve as inspiration, always struck me as depressing; here in these shabby Car Barns and Burger Huts of America, people stuck in these high-pressure, low-stakes, mostly unrewarding jobs had actually applied themselves.

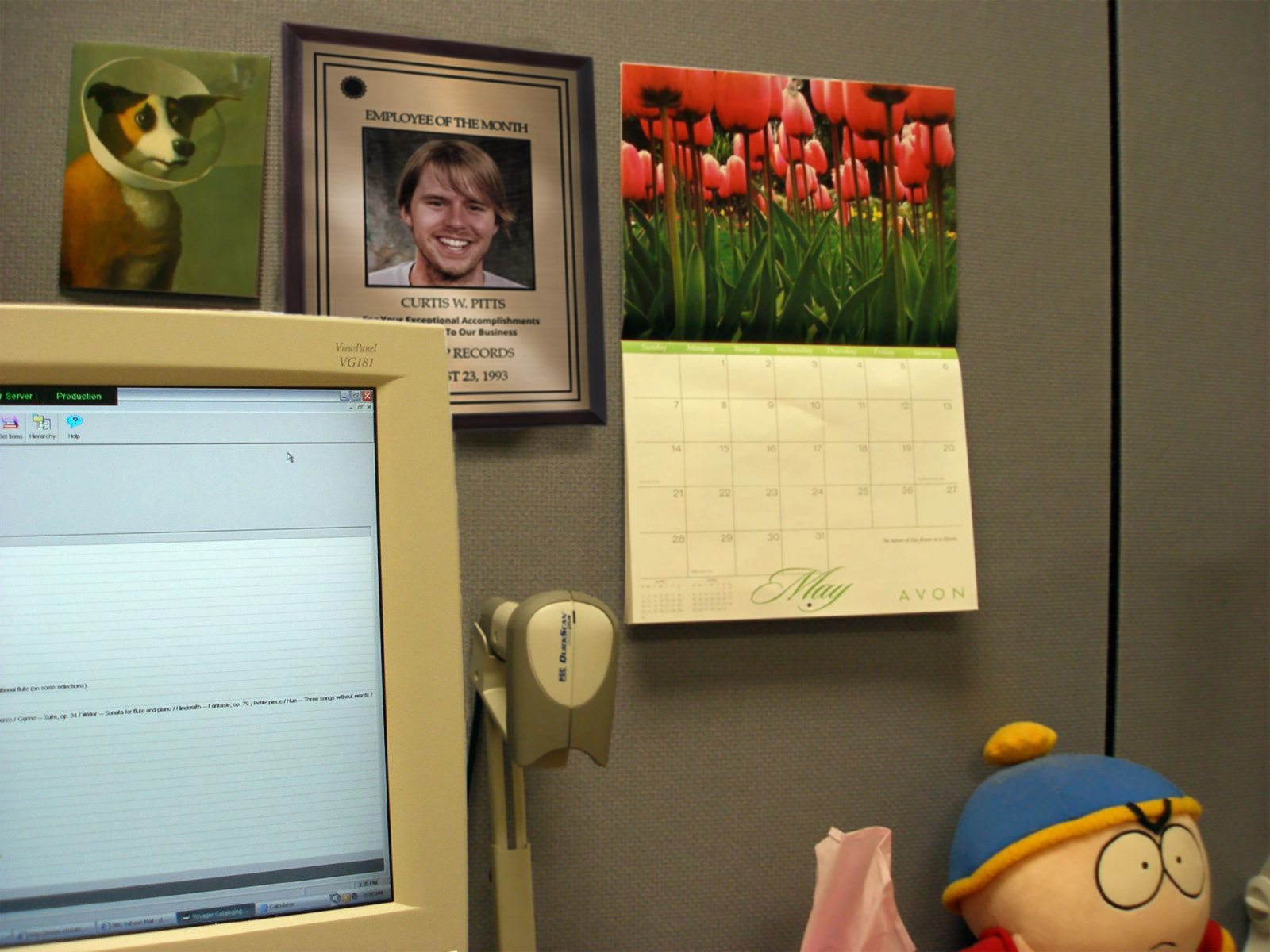

This is part of what made the Sub Pop label compilation Curtis W. Pitts: Sub Pop Employee of the Month stick out so memorably when it was released in the summer of 1993. (Full disclosure: I did not hear the record until I was a freshman in college, in 1997.) The idea of an indie record label—and not just any indie record label, but the one that discovered Nirvana—needing to reward its employees in any way, as if Sub Pop were just another fast-food joint or auto lot, was laughable. But it was also reassuring, a reminder that despite massive success, Sub Pop had not, in the parlance of the day, sold out. Before Beck, before even Nirvana, the label had made a small killing selling T-shirts emblazoned with just a single word: “Loser.” Releasing an album bearing the face of and named after one of its “star” employees was a way to signal that absurd success had not gone to anyone’s head.

Listening to the comp in college in the late ’90s, with Kurt Cobain dead, the first dot.com bubble about to burst, Starbucks starting its ascent to ubiquity and boy bands and rap rock taking over the radio, was a way to commune with the spirit of an era that, though less than a half-decade in the past, felt long gone. To listen, usually late at night, usually under some kind of baleful influence, to Sub Pop’s wildly optimistic idea of what the rest of the decade was going to sound like (a mix of international rockers, indie pop, electronic disco and woolly psych outings more in tune with this century than the last) while staring at Curtis W. Pitts’ devil-may-care smile—he resembled a less fate-kissed Kurt Cobain—was to immerse yourself in a universe in which losers could win, irony could save the world, success was a joke and the downwardly mobile could wind up calling the shots. Accordingly, Pitts became something of a patron saint and a folk hero in my friend circle. Helpfully included with the album were some brief biographical notes that only added to his mysterious, pseudo-sacred aura.

“I hate punk rock,” the bio quotes him as saying, painting a picture of a person who, like Sub Pop itself, seemed to inadvertently stumble into something comically lucrative. According to the bio, he’d gotten his job as “retail salesperson” when the position’s previous occupant, Pitt’s friend Aaron Stauffer, of Tacoma emo forebears Seaweed, left on tour. “I needed money to buy a vehicle I could live in so I could save money to buy land,” he says. Here was the ’90s dream personified: uncommercial, self-sufficient, plugged in. The bio adds that Pitts planned to move to land he was paying off in rural Fruitland, Washington, where he would “grow and gather food in relative isolation.”

My friends and I would wonder if Pitts had achieved his goal of genteel retirement, if, having reached the top of the world, he’d then vanished, like famed bank robber D.B. Cooper, who, bearing sacks of ill-gotten cash, had jumped off a plane over the Cascade Mountains in 1971, never to be seen again. Or perhaps seen, but not apprehended. Just as reports of Cooper sightings sporadically appeared in the decades following his disappearance, so my friends and I would keep an eye out for a certain shaggy, dirty-blond face at concerts. Could that have been him at the Built to Spill show last night? Maybe!

A few weeks shy of the 30th anniversary of the release of “Curtis W. Pitts: Sub Pop Employee of the Month,” I spotted Pitts for real, on Facebook, and he kindly agreed to answer questions that had been plaguing me for my entire adult life. The answers were not a disappointment, painting a picture of wild ambitions, slacker capitalism and disabused illusion that could only have happened in the early ’90s, when punk was still breaking and no one wanted it fixed.

At the time Pitts got his coveted job selling Sub Pop albums and accoutrements to mom-and-pop record stores, he “was a dishwasher at a vegetarian restaurant and living on the street in a camper,” a hardcore kid who’d made the pilgrimage to Seattle after almost-but-not-quite graduating high school. “This is right as Nirvana was popping off,” he tells me. Pitts had fallen into a job at a gold mine right before the first big strike. “Within a few months I put the down payment on my place, quit the restaurant and was selling shit tons of Loser shirts, Nirvana records and everything else,” he remembers. Pitts received a 1% commission off his sales, but even that meager rate adds up quickly when you’re selling candy that everybody wants. (On the day Cobain died, Pitts made $5,000—a staggering sum in ’90s money.)

He remembers the idea for putting his face and name on the comp coming from a Sub Pop employee, who now works for Meta and did not return requests for comment. It was an employee of the month “for the company’s most unemployable,” Pitts recalls. Pitts says Sub Pop co-founder Jonathan Poneman once asked him if he was the Unabomber—still at large in 1993. “I took it as a compliment.”

After agreeing to the project without much thought (“I thought it was funny…and said sure.”), Pitts grew to somewhat regret his hasty decision, as thousands of CDs, tapes and LPs emblazoned with his face hit the market. “It's a funny thing to see someone you know or recognize in some random image selling something,” Pitts says. (NOTE: This is the purest 1990s statement made in this article.) “So it was funny to people who knew, or sort of knew me. I did not feel like they were making fun of me, but the feeling was similar. I never let it get to me, because I had a great thing going, but, yeah, I got ‘It's the employee of the month!’ every day.”

With financial success and subcultural fame secured, Pitts was in a position to achieve his dream of yeomanly rural husbandry, but the biz wasn’t through with him yet. “Not too long after the employee of the month thing, and my place was paid off, [major label] Atlantic bought half the company and I was promoted to A&R agent,” he reveals. Artist & Repertoire people were the ultimate cool hunters, tasked with finding the coolest, newest bands and wining and dining them on the corporate dime. It was viewed by many at the time, and maybe even in these diminished days, as the pinnacle of Awesome Jobs, the paragon of “Can you believe I get paid for this?” gigs. The “unemployable” guy living in a camper had made it to the top of the heap. But, like many of his cohort, Pitts found success to be less than satisfying.

“Some people from the underground and hardcore scene gave me BS about ‘selling out,’ [NOTE: This is the second-purest 1990s statement in this article.] and other old friends were hoping I would sign them. It just was awkward. I got to where I did not like live music anymore. I burnt out. After a year, we had just spent money, and Atlantic said 'get rid of this expensive guy,' and that was that."

Pitts decamped for Fruitland, population 812, in the mountains of northeastern Washington, once home to Donnie and Joe Emerson, whose forgotten 1979 album Dreamin’ Wild, was recently reissued by another great Seattle label, Light in the Attic, to great acclaim. There, he’s cobbled together a life that, though not without its “ups and downs,” allows him the freedom and flexibility to do as he sees fit, for the most part.

“It's been a mix of total isolation, and needing to plug in and work some job, but half the time I've been self-employed doing odd jobs like selling firewood, landscape work and helping farms at crucial times,” Pitts says, admitting that he listed his employee of the month status on a few job resumes. This independent status gives him time to focus on what matters, like skateboarding (he’s built numerous skate ramps on his property) and snow sports. “I ride something called a ‘bi-deck snowskate’. It's a bindingless snowboard. I also am a ‘powder surfer.’ It's also no-binding snow surfing. I'm kind of a ski bum. I work for our local ski hill (49 Degrees North), but I'm done early, more hours on the board than on the clock.”

As for his former “celebrity” status, it still occasionally pops up. “Every once in a while, someone finds a copy of the record and sends me a pic, that's really cool—and the best thing was, after my father passed, my daughter and I went to [his house]. She has a little vinyl collection, so she was sorting out what albums [of Pitts’ father’s] to bring home. She came across it, had never heard of it, and was 'WTF?'—she read the back [which mentions Pitts’ intention to get a vasectomy], and laughed as hard as I've ever seen her. That made the whole thing worth it.”

Pitts has cashed in, slacked off and dropped out, and it’s left him with an enviably clear sense of what matters and the necessary tradeoffs involved. And speaking of the big picture and important questions: Does he still hate punk rock? Well, during the time of our email exchanges, he made the 73-mile drive to Spokane to see the Circle Jerks.

~

Photo illustration contains elements from Cubicle Wall3 by mcdlttx on Flickr.

Reed Jackson is a syndicate editor who lives in Kansas City, where he is often mistaken for Adam Savage. He writes for what remains of legacy music magazines and alt-weeklies, as well as a few websites of specialist bent. His likeness has appeared in more than one newspaper comic strip.