If you’ve seen it—and once is most definitely enough—it’s hard to forget Ellen Burstyn’s performance in Requiem For a Dream. Harrowing, wild-eyed, hiding from her seemingly sentient refrigerator, her Sara Goldfarb, a lonely widow, just wants to fit into her red dress, a worn symbol of better times. She wants to be seen. Sparked by the desire to lose weight, her drug addiction leads her into utter psychosis, and we are there, watching her fall apart in close-up.

She’s so raw and human, so close to the bone, and to even be reminded of the character is to physically feel pain about the human condition. We are so fallible, we have such simple dreams, and yet, we fail. But Burstyn doesn’t in her performance, the very definition of brave. It stings a little bit that she lost the Oscar to Julia Roberts as Erin Brockovich—a case of the movie star winning, and not the haunting performance.

For the last fifty years, Burstyn, now 91, has been an indelible presence in American cinema. She was the star of a film that I can’t ever see because I am a weenie—The Exorcist—-and she starred in the reportedly dreadful sequel that came out last year, fifty years later, where she asked for double the pay so that she could fund a scholarship program for young actors working for their M.F.A. at Pace University.

If Ellen Burstyn had simply been the star of The Exorcist and Requiem For a Dream, that would have been enough. But those two films are just a sliver of her long career on screen, something that came along years after she established herself on stage. Born Edna Rae Gillooly on December 7, 1932 in Detroit, Burstyn worked as a model, a dancer, and ended up with her break on Broadway in 1957 where she was a “fresh and attractive heroine,” according to Time Magazine, in Sam Locke’s Fair Play. She would go by Ellen McRae until she married Neil Burstyn in 1964.

The beginning of Burstyn’s career was mostly small jobs on TV and in film, and she could have gone the typical starlet route—but the spark to her art occurred when she started working for The Actors’ Studio and studying with Lee Strasberg in 1967. She described a “voice in my head” in an interview with Isaac Butler, which was the impetus to move away from Hollywood, back to New York, and to take acting seriously. She was cast in Peter Bogdanovich’s The Last Picture Show in 1971, where she played mom to a luscious Cybil Shepherd. She came into film as a full-grown woman, getting her break around 40.

In 1975, she won an Oscar for Alice Doesn’t Live Here Anymore, one of those ‘70s pure cinema marvels that feels like a real, vivid moment in a struggling woman’s life: Alice is a single mom, a waitress, an aspiring singer, who falls for a hunky Kris Kristofferson. Burstyn considered directing it, but it ended up being a Martin Scorsese film, his follow-up to Mean Streets, and he got the job by saying that even if he didn’t know anything about women, he was willing to learn. To this day, Burstyn is the only woman who Scorsese has directed to a Best Actress Oscar.\

Years ago, I had a job that required going to press junkets for movies. Junkets are a tricky beast. Actors, directors, and writers talk to journalists about their new work in 10 minute increments. Most often, the questions the journalists ask are related to the press kit that they have already read. It is a repetitive and boring day, a dance where everyone dully knows the steps, and it’s hard to get anything good, interesting, or genuine out of a press junket. Strange interactions occasionally go viral—think Jesse Eisenberg’s barbed hostility towards a TV interviewer, things of that sort—and they go viral in the context of oh, that person is being mean and rude while this other person is trying to do their job, but trust me: a press junket where an actor goes off script is, at this point, actually exciting.

The fifth circle of hell is a press junket where the actors do roundtable interviews, where you sit at a table with five other journalists and get in one question. The People intern will awkwardly ask about someone’s baby joy. Someone whose website is little more than Bob’s Big Flick Pics will ask the actor to take a photo with them. It is difficult to feel like anything close to genuine conversation is happening; and I did this for over a mind-numbing year. However, every so often, someone would be able to overcome the inherent, already scripted awkwardness and come off like a real person who could command a table: I counted Anne Hathaway, Paul Schneider, Ben Whishaw, Jane Campion, Jeffrey Wright, Mos Def, Gael Garcia Bernal, and the late Jonathan Demme, as some of the rare figures who could cut through the robotics. To my mind, there was one person who I met that year whose presence was so regal, touched, as if she had things and life already figured out, that I merely needed to be feet from her to bask in her reflected glory, and that was Ellen Burstyn.

Do I remember many specifics from my roundtable interview with her? Absolutely not. It was for a tiny indie with Bryce Dallas Howard and a pre-Marvel Chris Evans, a lost Tennessee Williams script that finally got to screen called The Loss of a Teardrop Diamond. It was hothouse southern hokum lensed in vaseline, and it got me in the same room with Ellen Burstyn, and it was that day that I understood what it meant to have the quality of presence.

She listened to people. She paid attention and she talked clearly. She did not truck with fools and idiots. She wore an outfit that I dimly remember as flowing, in expensive fabrics, and she was beautiful. Radiant. She was probably in her late ‘70s at that point, and I left determined to find out more about her. I picked up her autobiography Lessons in Becoming Myself.

Lessons in Becoming Myself: now that’s a book! Burstyn goes into detail about the difficulties she faced growing up, her experiences with abuse, her journey to acting and her iconic roles—and there is also a streak of wild, Shirley MacLaine-style mystic stuff. Burstyn practices Sufism. She meditates. She does a retreat that involves rough sleeping on the street, in order to experience the difficulties of unhoused people’s lives. She is earnest! Last year she told Chris Meloni in Interview Magazine that she was “overly honest” in it. I didn’t think that was the case—she was real, and she revealed the things that she overcame and the ways that she holds herself up, all truths that people can connect over. But reading her biography did make me search out her 1980 film, Resurrection, where she plays a woman who becomes a healer after a near-death experience.

Is Resurrection a good movie? I’m not quite sure. But it’s a fascinating movie—with a sexy, laconic Sam Shephard— and renders a near-death experience as a great beyond with bisexual lighting and the people that you knew and loved surrounding you in a flickering strobe. And Burstyn is incredible, finding the truth in every moment. She has these scenes that are quiet—she’s simply trying to will her broken body to work again, for her legs to walk —and it’s riveting to watch how she sits and imagines; it makes me think about the role of healing and love and the energy that’s flowing through the world.We could all stand to learn a little bit more from the way that Ellen Burstyn holds herself in the world, and I look forward to what she can get out of her ‘90s—a casting agency that I follow online has been looking for a stand-in for a 91-year-old actress, and I know it’s Burstyn, working hard, living a healthy life, and practicing her art, all to reveal some more mysteries about human connection.

Elisabeth Donnelly is a journalist, author, and screenwriter living in Brooklyn with her family. She has written features, interviews, and reviews about topics like ragdoll cats, loneliness, artistic swimming, Gilmore Girls and David Lynch, art models, and movie posters for publications including The New York Times, The Believer, The New York Times Magazine, The LA Times, The Paris Review Daily, Vulture, The Cut, Dirt, and more. She is working on a novel and thinking about writing a newsletter.

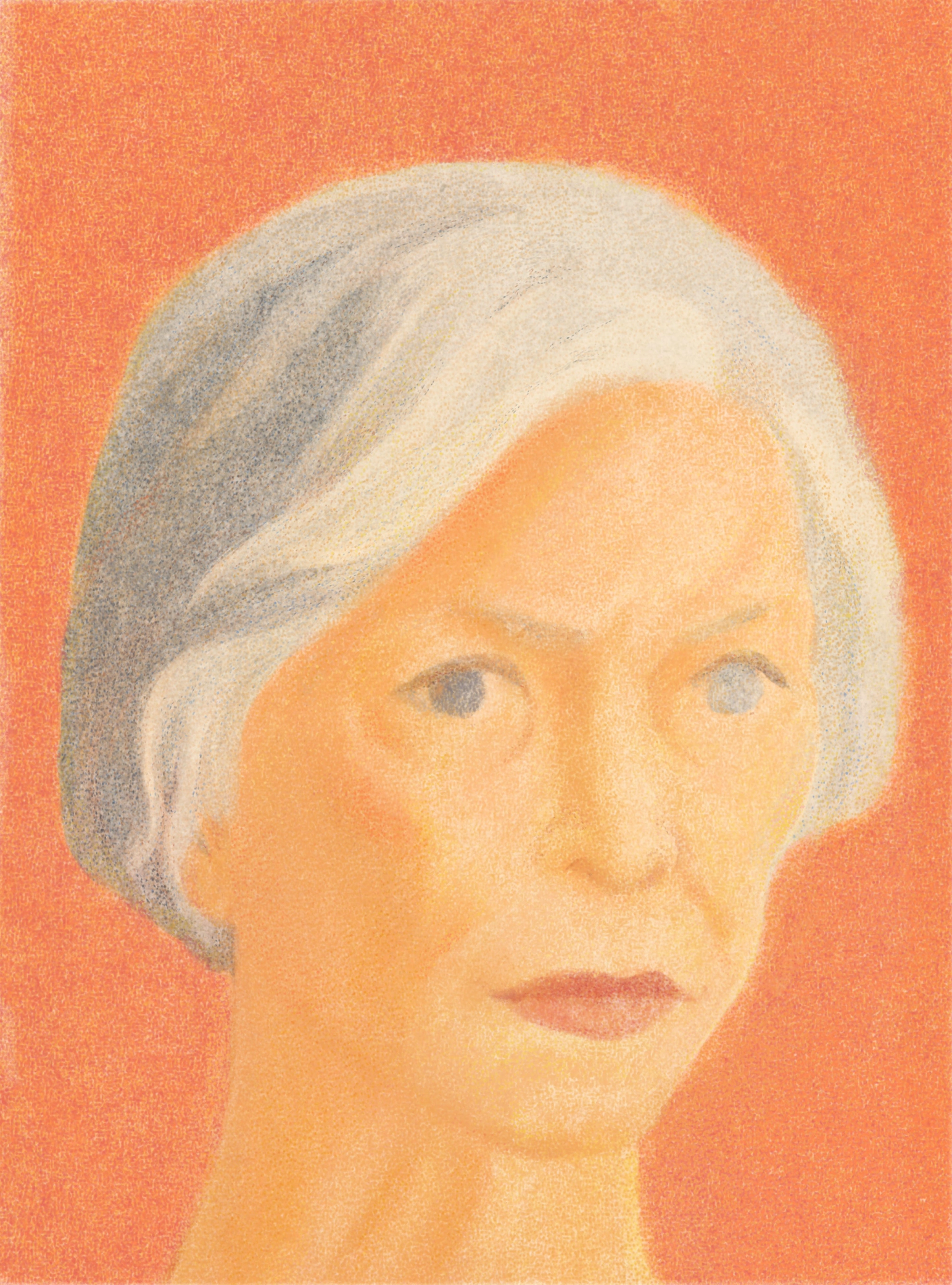

Art by Calli Ryan