I hold an unusual piece of American trivia that I like to offer whenever conversation allows. It is a good fact to relate, ideally over drinks, because not only is it interesting on its face but it’s strange enough that it can alter how one thinks about American history, if only temporarily.

The trivia is this: There’s a man living in Virginia whose grandfather was John Tyler, the 10th president of the United States. Not great-great-great-grandfather, not great-great-, not even a single “great.” Just a regular grandfather, the father of one’s father. Tyler, who was born before the ratification of the Bill of Rights, became president in 1841, and died just three years before Abraham Lincoln’s assassination, has a living 94-year-old grandson named Harrison Ruffin Tyler.

If all that isn’t mind-bending enough, things get stranger when you hear that Harrison Ruffin Tyler’s great-grandfather (President Tyler’s father) was roommates with Thomas Jefferson at The College of William & Mary. It is wild to think that there is a living person who has a familial connection, just three generations back, to our third president, a Founding Father born in 1743. It is also wild to think that people had college roommates in the 1700s.

***

By now you’re trying to do the math. That’s what everyone does when they first hear this trivia. But it’s not actually that complicated; it just involves old men having children with much younger wives.

John Tyler was born in 1790 and had 15 children (the record for a US president). One of those 15 children, Lyon Gardiner Tyler, was born in 1853 when Tyler was 63. Just like his father, Lyon Gardiner Tyler would go on to have children into his twilight years, and in 1928, at the age of 75, he sired Harrison Ruffin Tyler.

In spanning the years 1790 to 2023, these three men have witnessed nearly the whole of United States history.

***

From many tellings of the John Tyler Thing, as I’ve come to call it, I’ve noticed that some people check out after you explain the math. Sure, it’s an interesting fact that Harrison Ruffin Tyler is a living link to America’s early history, but it’s no more than that—mere trivia.

But that is not the most common response. More often the fact is met with a sense of wonder. While part of that is from the heady math—perhaps heightened by the drinks, if drinks are present—I don’t think that’s truly what impresses people. After all, anywhere in the world it is possible that successive generations of very old men are having children late in life, resulting in a similarly long three-generation run.

No, there’s more to it. I think what’s going on with the John Tyler Thing is that it obliges you to reckon with what such a thing says about America. For most humans, the stretch of time and history is hard to feel, even when it comes to the major events we use to mark eras. The Revolutionary War, the Civil War, Reconstruction, even something in the 20th century like World War I—do we really sense how long ago those things were? Maybe if you’re a Ken Burns or a Doris Kearns Goodwin, but for most of us who don’t go about our lives making a study of history, even major events are difficult to place in time. But when someone says to you, “There’s a guy down in Virginia whose grandfather was born when George Washington was president,” it brings time down to a human level. It makes you feel viscerally how young we are.

***

Before I knew about the John Tyler Thing, there was another unusual generational overlap I used to think about that illustrates the shortness and strangeness of American time.

In 1941, Robert Allen Zimmerman was born in Duluth, Minn., where he lived with his family on North 3rd Avenue. He was born in spring, so it’s likely that many of his very earliest days were spent with his parents strolling him around their residential neighborhood. If, on one fine spring afternoon, Robert’s parents took a certain route from their house—one block towards Lake Superior, hook a right on East 5th Street—then baby Robert and his parents would’ve landed right in front of the house belonging to Albert Woolson.

You probably know that this child, Robert Zimmerman, went on to become Bob Dylan. But you may not know who Albert Woolson was. When he died in 1956 at the age of 106, Woolson had been the last living Civil War veteran.

What is the link between Woolson and Dylan? I grant that it is mostly geographical and much more tangential than the blood connection between President Tyler and his living grandson. This link is mystical. Dylan’s music draws on some of the earliest American musical traditions and themes, going back to the Civil War and even earlier, and it seems magical that someone still extending those ideas into concert halls around the world once lived alongside a veteran of our existential war. Two houses in Minnesota, just 469 feet apart: in one, the last relic of America’s bloody and still-unfinished self-examination, in the other, a boy who would grow up to shape American culture in profound ways. Like President Tyler and Harrison Ruffin Tyler, the situation presents us with an overlap of past and present that seems uncanny and maybe even disturbing. Or maybe it’s just fascinating—fascinating to think that Woolson and Dylan lived in the same nation as literal neighbors, fascinating to think of one man handing the baton of American history to the other, if only cosmically.

Another example, on the evening of February 8, 1956, CBS aired an episode of I’ve Got a Secret, a live game show in which a contestant with some interesting personal history was quizzed by celebrity panelists trying to figure out the contestant’s reason for appearing. On this February evening, the contestant with a secret was Samuel J. Seymour, who at age five had witnessed a historically significant event.

“Was this a pleasant thing?” asks one of the panelists, actress Jayne Meadows.

“Not very pleasant, I don’t think,” says the 95-year-old Seymour. “I was scared to death.”

Meadows soon figures out what had so scared Seymour. She looks delighted; the audience applauds.

But it is the audience reaction slightly earlier in the episode that really gives you chills. The format of I’ve Got a Secret is such that the studio audience (and the audience at home) is let in on the secret before the panel’s guessing begins. And so when a text overlay appears—I SAW JOHN WILKES BOOTH SHOOT ABRAHAM LINCOLN—you can hear the audience’s shock and you can imagine the collective gasp of tens of millions of Americans in the 12 million homes who watched CBS that evening.

A good number of those 12 million homes were also likely tuned to CBS 11 evenings earlier to see Elvis Presley’s television debut. Imagine that: watching “Shake, Rattle and Roll” for the first time and just a few days later gathering around the same television set to see a man who nine decades earlier had witnessed Lincoln’s assassination.

***

At The College of William & Mary—where Thomas Jefferson and Harrison Ruffin Tyler’s great-grandfather once shared a ... dorm room, I guess?—the history department used to be named in honor of Harrison’s father, Lyon Gardiner Tyler. In 2021, William & Mary renamed the department due to Lyon’s racism and defense of the Confederacy. Another building, Tyler Hall, named for both Lyon and President Tyler, has also been renamed.

John Tyler’s name has been removed from almost every building, road, or school once named for him. Nothing new will ever be named for him. Born to slaveholders, Tyler became a slaveholder himself and was a representative-elect of the Confederate Congress upon his death. He has the dishonorable distinction of being the only president whose passing was not officially recognized in Washington, D.C., and he was the only one laid down under a non-United-States flag—his was Confederate.

A few years ago, William & Mary decided to take Lyon Gardiner Tyler’s name off of their history department. They renamed it for Lyon’s son, Harrison Ruffin Tyler, a man who has spent part of his life making a public museum of his family’s plantation but who also agreed with William & Mary on the need to remove his father and grandfather’s name. A man who is a 94-year-old link to our dreadful past, but not of it.

***

I was raised in the 1990s. What luck. Things felt good. They don’t anymore. They haven’t since the end of my high school years, when 30 miles away, the towers fell. America in this century has filled like a stagnant pool with confusion, rancor, and a lack of kindness towards one another.

I don’t find it easy to come by hope for this country, not necessarily. American life is too hard and expensive and murderous, and we contain too many systems that seem beyond repair.

But hope is the American currency, and I try to pick it up where I can. That’s what I find useful about the John Tyler Thing, and why I like to share it with others.

We live in a country in which one of our earliest presidents has a living grandson. If you allow it to, this perspective on American time can help you feel encouraged when examining our strange, infant nation. It invites you to think about our youth and where we may be headed. If there is still a man among us who can reach his hand back just two generations and brush up against our nation’s earliest days, why shouldn’t we have hope in knowing we’re still young enough to figure out who we will ultimately become?

Josh Lieberman lives in Beacon, NY.

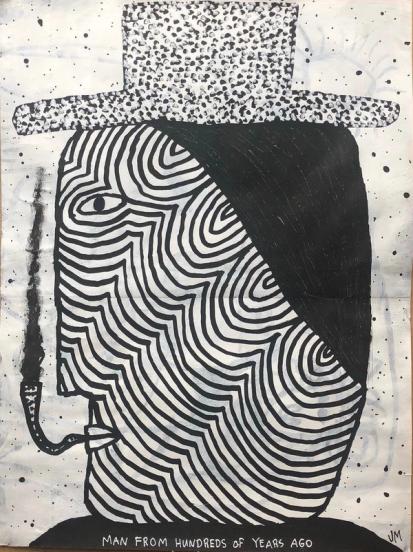

Art by John McKie.