in the first slide, I’m maybe six years old in the living room that no one ever sat in, with its modular 70s couches and animal-print pillows, wall-to-wall green carpeting, rubber-tree plants, and curios from my parents’ travels, including an impressive copper samovar on the hearth. My siblings and I would never understand the design scheme of this room, some cross between Elvis’s Jungle Room and a souk in Marrakesh. There is a tall music console in the corner, radio, double cassette player, turntable, speakers, buttons and dials that I love to punch and twist when I wander the house alone, which I so often do. Joan Baez’s voice is issuing from the speakers, and I’m staring at her face, which I can picture perfectly, on an album cover—which album, I can’t recall. I can hear the voice but not the lyrics. This is the nature of memory. This is also the nature of Joan’s particular sound, her relentless soprano more aura than music, more frequency than song.

In the next slide, I’m crouching beside my mother’s bookshelf at maybe eleven or twelve years old, paging through a copy of And a Voice To Sing With, the memoir Joan Baez wrote when she was 45, the same age I am now, and published at 46, the same age my mother was, if memory serves, and it usually doesn’t, when she bought and read it. I’m trying to corroborate something my mother had told me, which was that she and Joan Baez had been at the same school in Baghdad, in the same year at the same time, but had never met. In the slide, I find evidence that my mom and Joan were classmates—the name of the school, the timeline, the precision of a perfect coincidence, rife with meaning I’d unpack later. I close the book with a sort of dazed joy, feeling famous, the world suddenly mine for the taking.

Those slides, vivid in my mind as any fact learned from a textbook, are largely, as with any memory, fabrications. The first one is less false, or at least unprovable. No one knows but me and that strange, empty room. The second slide is problematic. Very recently, I read And a Voice To Sing With in its entirety. I felt my pulse quicken as I approached the pages detailing the Baez family’s time in the Middle East. It was 1951 and Albert Baez (“Popsy”) was commissioned by UNESCO “to teach and build a physics lab at the University of Baghdad.” I read and reread young Joan’s impressions of her new environment, the hepatitis she contracted and mashed black bananas that helped her regain her health. In Joan’s final assessment, “Baghdad was a melancholy place,” though she later recalled, when criticized for not depicting the city in a more flattering light by an Arab woman who’d read Joan’s earlier memoir Daybreak: “How when the winter was over, we kids moved our beds out to the roof, and through the musty-smelling mosquito net I spoke to the stars, telling the Big Dipper things I could never tell any person.” If you ask my mom about her childhood, the first thing she’ll tell you is how they slept on the roof (she never mentioned mosquito nets, or mosquitos), the closeness of the stars, the awe she felt that never diminished. How curious to imagine her mere rooftops away from Joan Baez, their secrets commingling in the night.

As for the details—I got close enough for them to blur into an approximation of truth. According to recent texts from my aunt, Joan did attend the school, was placed in the foreign section where they taught English and French but not Arabic, and was expelled, or “left after an argument with Sister Rose, the director.” Joan’s memoir doesn’t, actually, as I remembered it had, include the name of the school, but my aunt supplied it—Presentation Convent School for Girls. My mother, 10 months older than Joan, may have crossed paths with her or her sisters, but there’s no way to know. I think I’m more charmed by their proximity than I would be if they’d been chums. The romance of a missed connection is much more interesting than the prosaic finitude of a real encounter. Later, my mom went to University of Baghdad for college and medical school, where she met my dad. Possibly they sat together in the physics lab built by Albert Baez.

When someone you love is unknowable to you, you learn to know them by what they love. My mother’s interests so rarely had anything to do with me, with her adopted country, with modernity. As an immigrant, she couldn’t embrace the zeitgeist of the sixties, but she had a passion for Joan’s early songs, twenty years after they were recorded. Baez’s voice in our house was anomalous and therefore, to my young ears and young sense of everything, captivating. Aside from Joan, music to my mother mostly meant hymns. My father’s singular fandom was for Umm Kulthum, whose iconic vocal style overwhelmed me, at that time, with melancholy and confusion. He disliked Joan’s strident, self-righteous soprano. My mother’s singing was also high-pitched, a nuisance to me when I stood next to her in church and wanted to hear my own voice. Her shrillness really came out when they fought, which they did a lot in those days, and I somehow think Joan Baez’s voice triggered my dad into a kind of layered disdain: for Joan, for my mom for liking Joan, and for the shared quality of their voices, a timbre that refused to be bossed.

Then there is the fact that I wrote Joan Baez into my 2017 novel Motherest for no other reason that I can explain, beyond the self-determined knowledge acquired by writing a novel: all of the pieces of yourself that have created your fundamental worldview up until that point will want to come out, to vie for their place on the page. Joan in Motherest is a girl that our heroine Agnes meets in the music library. Agnes calls her Joan privately at first, not knowing her name, because she looks to Agnes like Joan Baez, who was a polarizing figure in her home (her dad loved her, her mom didn’t—the opposite of how it went in my home). Only later does Agnes find out that the lookalike’s name is, actually, Joan. I don’t know; I had fun with this. I even found a way to include “Sweet Sir Galahad,” one of my earliest favorite Baez songs, which she wrote for her sister Mimi on the occasion of her second marriage. Clearly, I’ve wanted to talk about Joan Baez for a long time.

Engaging with Joan is a way of engaging with my mother, whose dementia has, at the time of my writing this, advanced to an almost unbearable degree. (She bears it; we struggle.) Her dementia is the result of nearly two decades of life-saving leukemia medication, a cruel coda to years of pain and anxiety. None of us knew that as her life was being saved, her mind was being poisoned, eroded. In bygone moments of clarity, she has asked me, fretfully, what was I supposed to do? Not take the medicine? But the clarity is becoming rarer, the curtain lowering fast.

Joan Baez’s life of radical pacifism, sexual freedom, and eventual fame bears little in common with my mother’s, who adhered to a staid and rigorous morality, graduated top of her class, and went on to maintain a conventional career as a physician. But everyone who knows my mother considers her an artist, a polymath whose painting practice and decades-long study of philosophy and theology, as well as her fluency in five languages, drew people and experiences to her in remarkable ways. There is something spiritually similar between them that I’ve been trying to identify. I think it’s how they are both so themselves—the candor, brightness, and unabashedness of Joan Baez was what, I think, filled stadiums, as much as, if not more than, her singing, and these, too, are my mother’s qualities, the ones her disease is taking away from her. Joan kept showing up with her smile and her guitar, no tricks, no drugs, no drama. She never tired of connecting to people, in bomb shelters in Hanoi or in sold-out stadiums, in her singular way, and she never really changed her sound or even her repertoire. Right before her 2019 Berkeley performance of “Diamonds and Rust” with Lana Del Rey, she comes out and greets Del Rey with a hug and a kiss, and then turns to the crowd: “Hello, children.” The two encore with “Don’t Think Twice, It’s Alright” and unquestionably, Joan’s voice is lower and wearier than it was when she first recorded that song. But still, she’s singing it.

Listening to Joan Baez’s early versions of “Love Is Just a Four-Letter Word,” “Farewell Angelina,” and other Dylan songs is wholly different than listening to Dylan sing them. Later, my mom and I would both love Dylan, but we heard Joan sing his songs first. Joan’s plaintive, sustained notes make them sound like dirges, whereas Dylan, ever the joker, has made an entire vocal register out of smirking. Baez calls Dylan, throughout her memoir, her “blood brother,” and certainly their relationship as she details it, including their early dalliance when Dylan gave her the blue nightgown belonging to Sara, is a highlight of the book. But it also sheds light on why his songs, in a certain way, perfectly belonged to her. She gave the world an intimacy with Dylan that it may not otherwise have been able to attain, fond as he is of being a trickster, trying on different masks, slipping out of reach. Dylan made art, and Baez became a consummate room in which to hang it. Maybe that’s really reductive and unfair to say, but I learned about art in that room, with my mother.

As I grew up, I left the room. My mom believed, probably believes still, that art has a responsibility to beauty and goodness. I began believing, believe still, that art has a responsibility to nothing but itself. But when I look, when I listen—I’m looking and listening for beauty, for goodness. I’m looking for my mother, remembering when we agreed on the sound of a voice, the turn of a phrase. Joan sang to us both.

Kristen Iskandrian is the author of the novel Motherest (Hachette, 2017). Her work has appeared in The O. Henry Prize Stories, The Best American Short Stories, Zyzzyva, Poets & Writers, McSweeney’s, Electric Literature, and many other places. She lives with her family in Birmingham, Alabama, and co-owns the bookstore Thank You Books.

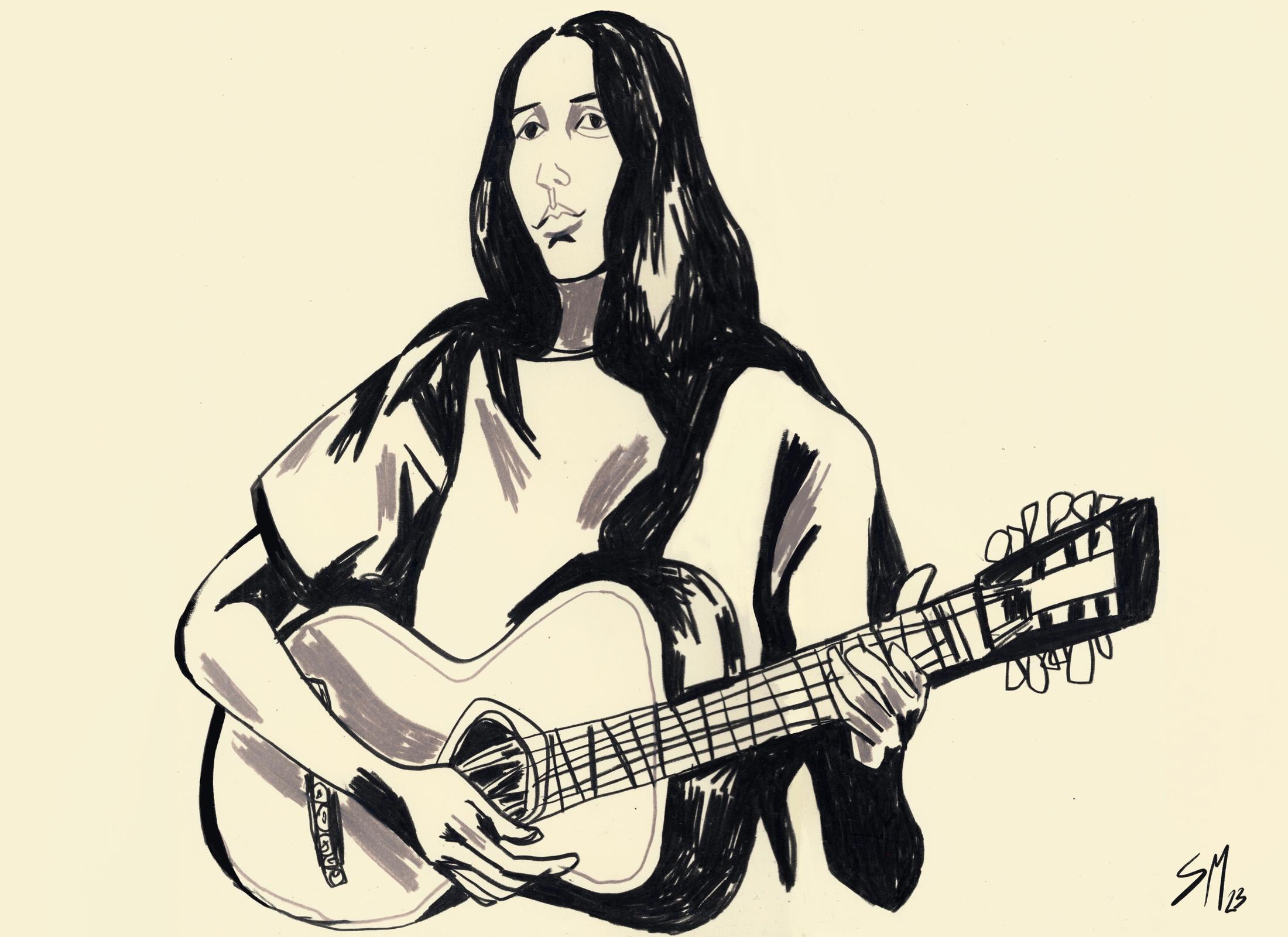

Art by Sarah Mari Shaboyan.