If I got lost during the parade commemorating the summer solstice, I knew to meet my mother at Vladimir Lenin. Sixteen feet tall, the bronze statue of the Russian Soviet leader towered over the throngs of naked bicyclists in body paint riding through closed-off streets, our neighborhood’s way of celebrating nature every June. I’d wind my way to his feet set in a permanent stride, as if about to charge onto the central avenue of Fremont in Seattle, Washington. My parents must have explained a dumbed down version of communist Russia, but to my child self the structure signified familiarity, a symbol of my world that wasn’t yet outside of me, one point on a crayon-colored treasure map of sense-based references—drawn between the corner store that stocks Strawberry Shortcake bars, the playground with the most slippery slide, and the fir tree where fairies like to hide.

Formally, the statue is not a very special work. On the surface a run of the mill commission by the Communist Party of Czechoslovakia, it was on display in the city of Poprad for a year before it was tossed to the scrapyard after the changing of the political tide. In 1993, an American teaching English in the region found it, with a homeless man living inside, and, for not entirely clear reasons, resolved to save the statue on the basis of artistic merit. (There clearly is craft in the textured folds of his jacket and the abstract-ish frame of firearms and flames that he emerges from.) Arrangements were made with the city and the artist, Emil Venkov, and the man mortgaged his house to ship it to his home state of Washington. He died in a car accident a year later, but before his family could melt it down to metal, a young sculptor rescued it again, organizing its eventual display on a prominent corner between a taco shop and gelateria in 1996, which, though the restaurants have changed, is where it stands today.

I was born across the lake in 1997 but I’ve long since left the Pacific Northwest. When people ask me if I would ever move back, I avoid directly answering but I tell them it’s not the place I knew. I know it’s not what it was before me, either. Seattle changed and keeps changing, and Lenin remains, tentatively. The statue is technically for sale, listed by the Fremont Chamber of Commerce at $250,000. While I’ve never heard of anyone making an offer, plenty of people claim to want it gone.

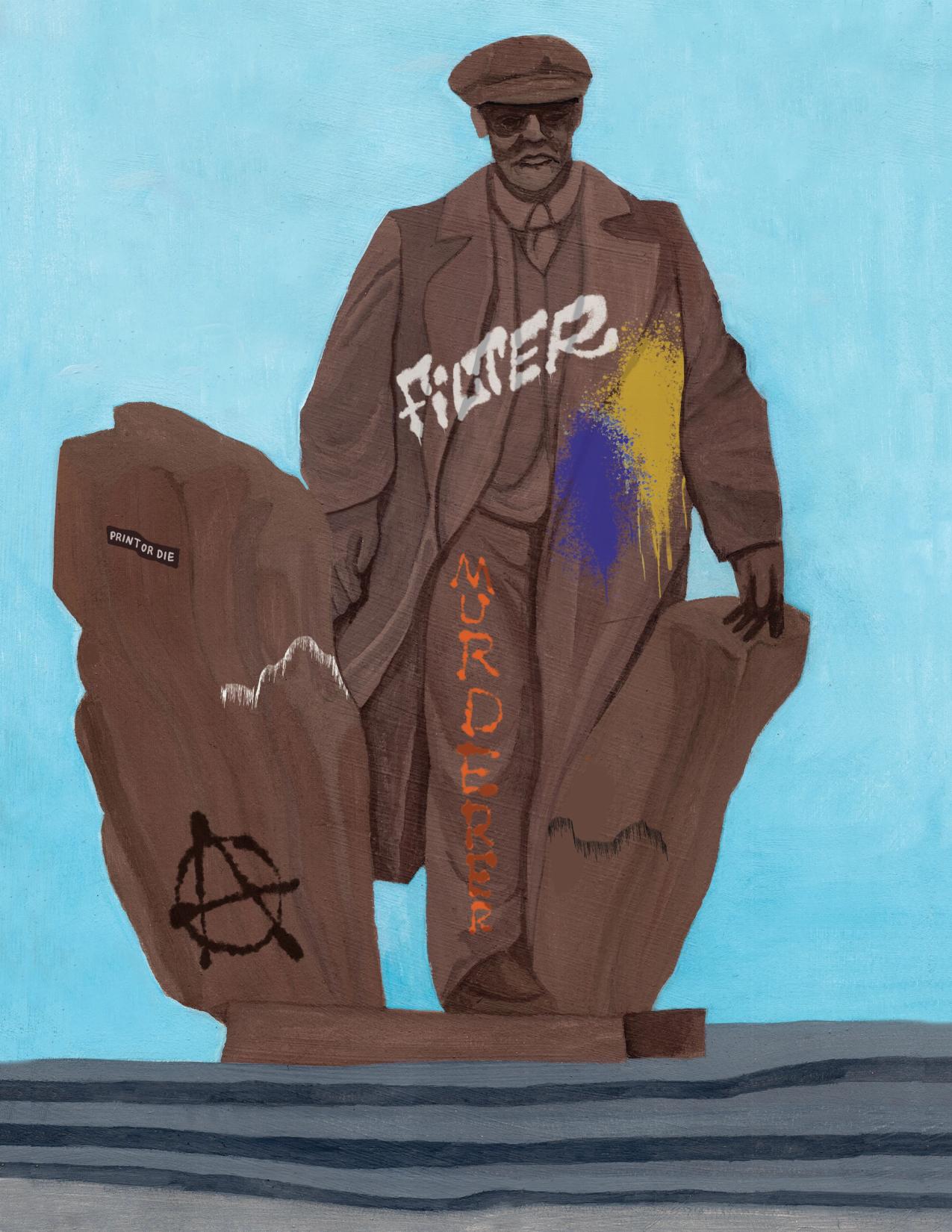

When protestors in Kyiv toppled renditions of Soviet figures, the internet asked Fremont if blue and yellow paint splashed across Lenin’s jacket was enough to signify what side it was on. Last year, a transplant hired at the Seattle Times wrote a column wondering why blue state hipsters protect a statue of a “homicidal tyrant” when we cheer the removal of Confederate monuments in the South. He ate pelmeni dumplings at the shop just behind Lenin (a restaurant I worked at for a summer) and felt sick that we “honored” a man who killed millions.

The writer doesn’t seem to understand that context is a fundamental element of art. In removing and reinstating the sculpture, the ad hoc artist coalition made a piece anew, one that collected its own history relevant to its adoptees.

In the late ‘90s, the artist Sophie Calle visited Berlin after reunification, after the government had established an independent commission to deal with the political monuments of East Germany—which usually meant taking down and disposing of them. She photographed the empty sites where memorial statues and plaques had been—including three dedicated to Lenin—and spoke to passersby about their memories and associations of what was no longer visible. They misremembered details: it was 20 meters high; it was 29 meters high. It was a brownish metal; it was chiseled grey stone. It was stolen; it was removed by local petition. They don’t talk about the GDR or the USSR, they talk about the physical relics of it: how they could spot the square head from the department store where their father bought boxes of ice.

A monument is made to legitimize the ideological, to make solid and strong the nebulous concept of authority, of one man ascending to power while everyone else suffers as his subjects. When that authority no longer exists—the man dead and his party toppled—the monument is no longer needed. The new ideology demands emblems of its own system in the public square. What we got to match the new Seattle: The Amazon Spheres, a geodesic and plant-filled office space insulated from the gritty downtown.

It’s been remarked that our Lenin is particularly menacing in the face, that Venkov included the guns to underscore dictatorial violence, whereas many renditions add a book in his hand or children at his feet. Venkov died in 2017 and never weighed in. But rarely is the statue presented as is, unvandalized. People use him as a prop for their varying agendas, draping him with beads and bras or spray painted slogans. I can look up the corner on Google Maps and scroll the years of Street View captures: in December he gets a tinsel wreath and a Merry Christmas sash; in 2017 a painted t-shirt saying something about “Mr. President”; in 2023, right under Lenin’s hand splashed with bright red paint, a shirtless man gives a thumbs up—presumably to a periscoped car as it captures his blurred out image.

The technology that allowed for this archive might have been coded a few blocks away, at the Google campus in Fremont. They have some art pieces dotting their private but visible grounds, and on sunny afternoons, employees wearing their key cards on lanyards play lawn games.

Tech found a home here. Quirkiness proved an attractive bonus for the upstart professionals asked to relocate to a place where afternoons are rarely sunny. There was an existing culture scene to take advantage of—art walks as the answer to their Thursday plans, the naked bike brigade that would lightly scandalize friends back east—without meaningfully contributing to the production or patronage of art themselves. This coexistence failed when the artists were priced out, unable to compete with those who are happy to live at a 50 percent higher cost than the national average. I like the thought of Lenin acting as a deterrent.

This defense is not about the commie chic; Lenin is but one character in the pantheon of Fremont’s monuments. Just south is a silver model rocket (coincidentally also Cold War era accurate) bearing Fremont’s motto: De Libertas Quirkas, the “Freedom to be Weird.” East is the Fremont Troll, a concrete monster clutching a Volkswagen Beetle in his hand as if snatched from the freeway above. (The piece won the neighborhood council’s 1990 competition to create an artwork to replace the mattresses and broken bottles under the bridge, which didn’t go away; tourists just step around them to get the shot.) On another bridge, a neon Rapunzel lets her hair tumble down the side of a control booth. Off the bike path are two grazing dinosaurs made of twisted ivy.

“The disappearance of the plaque doesn’t change the fact that he studied there,” one Berliner told Calle of a plaque commemorating Lenin now removed from Bebelplatz Library. If the Lenin statue disappears from Fremont, it won’t change the fact that Seattle welcomed what didn’t belong anywhere else. American cities have never looked more alike, their main drags populated by the same soap stores and salad chains designed to be totally inoffensive. Let the controversy stay, provide purpose for a place amidst dwindling reasons to travel at all. And if it’s a return to place, all an émigré can hope for is someone else who remembers. Sometimes the best she can find is a sternly silent man cast in bronze.

Greta Rainbow is a Seattle girl living in New York. Her essays, criticism, and reporting on arts and culture have appeared in the Guardian, the Los Angeles Review of Books, New York Magazine, and the New York Review of Architecture, among others.

Art by Kees Holterman