When the writer Milan Kundera died on July 11, 2023—while I was writing a piece about him being still alive—the forgetting of him began with a mass remembering. For one day, papers, magazines, and social media were covered with Kundera. And then he began to disappear.

Maybe it’s fitting for an author so clear-eyed about our need to forget. In The Book of Laughter and Forgetting (1979), Kundera begins by listing historical events that made us forget their predecessors: the assassination of Salvador Allende made us forget the Russian invasion of Czechoslovakia, and the Bangladesh genocide made us forget Allende, and the Yom Kippur War made us forget Bangladesh, “and on and on, until everyone has completely forgotten everything.” It’s an exaggeration; we don’t forget everything—just most things. But the first time I read the novel, I had to look up all the events Kundera listed. The passage reflects Kundera’s view that life is absurd—how else could something that feels like the most important thing in the world vanish just as quickly as it appeared?

I’m often hesitant to tell people how much I love Milan Kundera. That’s because he does things like compare the “sudden density of life” of reading Dostoyevsky to the “rare, dream-like” occurrence of making love to three women in the same day. (Oh, that density of life!) But despite these moments, from the time I first picked up Kundera as a 21-year old—and found, to my delight, that the big ideas that I’d only seen buried in unbearably long paragraphs by humorless Germans could instead come in fun-size bites—I’ve been unable to put him down.

Kundera mixes the high and the low with such joy. He loves white space and paragraph breaks. He wrote in Testaments Betrayed (1993) that he wanted to write novels in which “the bridges and the filler have no reason to be,” essentially predicting the slogan of the fragment trend of the 2010s. When he tries to tackle life’s big questions—which he tries to do on pretty much every page—he’s not making fun of himself for being so self-serious as to try to decipher the meaning of life in a novel. He’s making fun of life itself.

“We live everything as it comes, without warning, like an actor going on cold,” he wrote in The Unbearable Lightness of Being (1984). “And what can life be worth if the first dress rehearsal for life is life itself?”* How ridiculous we are, trying to make sense of existence as we’re experiencing it! How absurd that we’re always doing something for the first time! We have no distance, no perspective, no second chance to live each moment. And yet we persevere.

Kundera persevered through loss of home and loss of language (though the latter was voluntary). In 1975, at the age of 46, he emigrated from his native Czechoslovakia to France, following years of government harassment, surveillance, and blackballing over his support for the Prague Spring; barred from even driving a taxi, he supported himself by playing jazz trumpet and writing pseudonymous horoscopes. It was in France that he published his greatest works: The Book of Laughter and Forgetting, about laughter and forgetting, and The Unbearable Lightness of Being, about time and getting laid.

In 1985, exposed to sudden fame, he swore off interviews and began withdrawing from public life. One of the last people to interview Kundera, a French journalist, recently emailed me out of the blue to tell that his dominant memory of visiting Kundera’s apartment back in the ‘80s was of the author’s paranoia—a paranoia the journalist believed was only found in those who’d suffered under dictatorships. (The ostensible reason for his getting in touch was that the journalist had just found an essay I’d published in 2015 in which I’d quoted his Kundera interview, and he wanted to tell me that my take on Kundera was “hooey” and “poppycock.”)

Kundera’s relationship to home was complicated. His work was banned in Czechoslovakia, and he was stripped of his Czech citizenship in 1979. In the latter half of the ‘80s, he began to write in French instead of Czech, first in his nonfiction, which is delightful and pretentious and silly and moving, and eventually in his novels as well.

Even though he managed the impressive feat of a midlife language switch, Kundera’s assimilation wasn’t easy. He was derided at home, where he was considered to no longer be a Czech writer, and though he himself wanted to be labeled a French author, the French seemed to prefer him when he was an exile who set stories behind the Iron Curtain than when he wrote about France.

In the early ‘90s, Janet Malcolm visited Prague and interviewed a writer who’d been forced into over a decade of window-washing after being blackballed by the communists—the same profession that Tomas, the protagonist of Unbearable Lightness, performs for two years, using the opportunity to sleep with countless customers.

“What [Kundera] wrote about window-washing was complete nonsense,” the window-washer told Malcolm. “Washing windows is very unpleasant work, and the women you work for do not sleep with you. The women you wash windows for usually regard you as the lowest scum.” He said that Kundera wasn’t a Czech author anymore. “He should write about France rather than Czechoslovakia.”

A newspaper headline in France from around the same time read: “Kundera, go home!”

But Kundera couldn’t go home. He had no citizenship and his work was both banned and ridiculed in Czechoslovakia. He tried to become French, but the French wanted an exile. His approach to this predicament was firstly, to tell the reader to worry about his work rather than his life (good luck with that!), and secondly, to laugh at it all. Life is absurd! We humans cannot know what a moment means until it has passed, and by then, it’s too late. “There would seem to be nothing more obvious, more tangible and palpable, than the present moment,” he wrote in The Art of the Novel (1986). “And yet it eludes us completely. All the sadness of life lies in that fact.”

“Before I left I was terrified of ‘losing home’,” Kundera said in an interview before he stopped granting them, “but after I left I realized—it was with a certain astonishment—that I did not feel loss.” He explained that he was happier in Paris than in Prague. And maybe he was—less persecution and all. But there’s a deep sadness to his writing—a heartbroken counterweight without which the humor would float away.

In his novel Ignorance (2000), Kundera wrote that in order to understand Odysseus, we must understand that he spent longer stranded on an island with his lover/captor Calypso than he did at home with his wife, Penelope. “And yet,” Kundera lamented, “we extol Penelope’s pain and sneer at Calypso’s tears.” It was, I think, a quietly autobiographical moment. Kundera wanted readers to care about his time away from Czechoslovakia—to care about Calypso’s tears the way they cared about Penelope’s. In the end, when he passed away at the age of 94, Kundera had spent longer in France than he had in Czechoslovakia—longer away than at “home.” But as he pointed out time after time, it is a function of life’s absurdity that one thing gets remembered while another is forgotten—that one chapter gets to matter while another does not.

Johannes Lichtman’s debut novel, Such Good Work, was a National Book Foundation 5 Under 35 honoree. His second novel, Calling Ukraine, is available in hardcover and paperback.

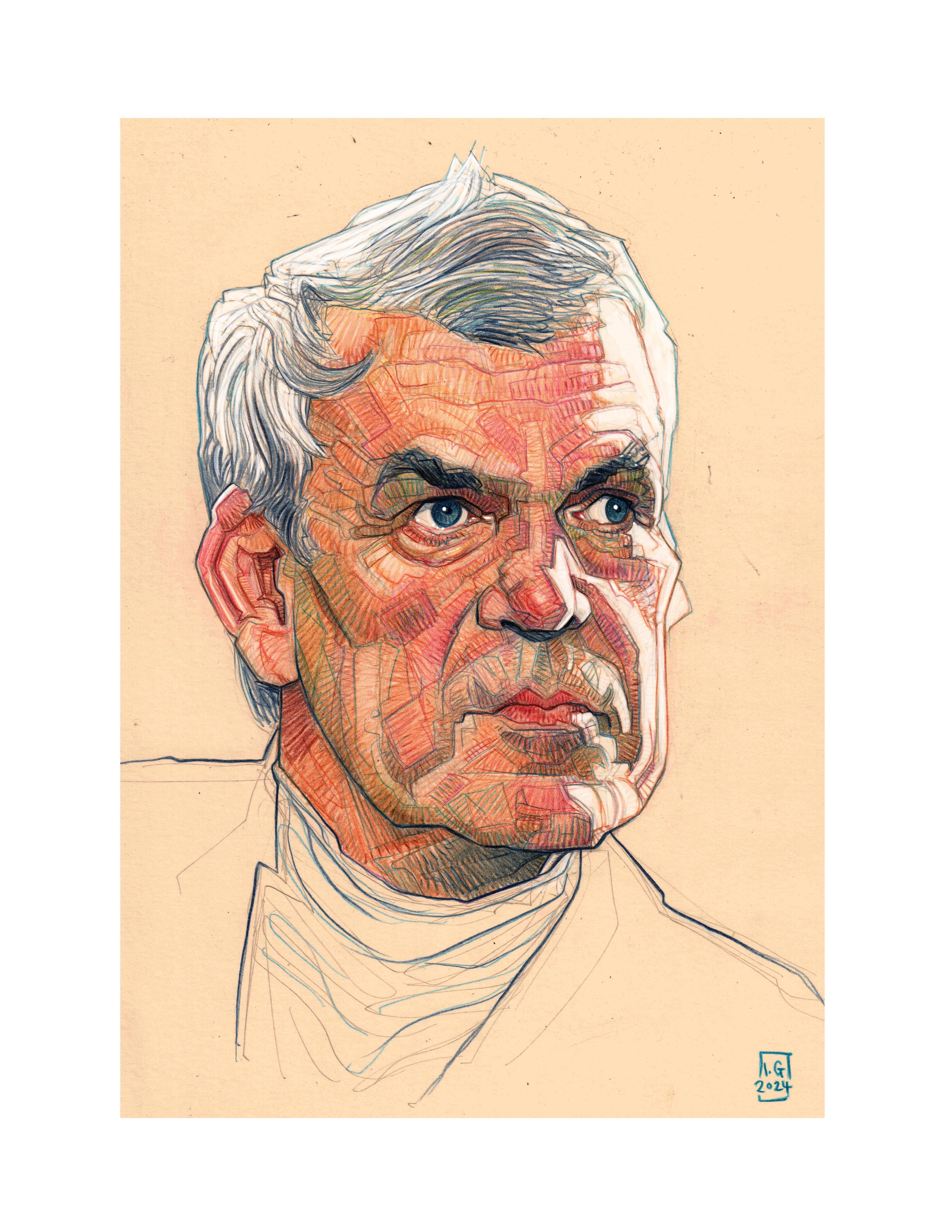

Art by Iddo Goldfarb