He was obsessed with Saddam—obsessed in a way that defied all reason. No one could talk him out of it. If Paul Wolfowitz was your friend, you'd take him aside and say: Wolfowitz, I’m worried about you. All Wolfowitz's friends were war-crazed neocons. They egged him on. One of them—a Harvard professor named Laurie Mylroie—published a book-length screed placing Saddam at the center of nearly all the world's terrorist attacks, up to and including the Oklahoma City bombing. At one point she offered her services to Timothy McVeigh’s legal team, on the assumption that McVeigh had been framed. Wolfowitz consulted on this book, blurbed it, pushed its repeatedly debunked claims on anyone who would listen. Track him through the Iraq War literature of the last 20 years and over and over again you'll find generals, analysts, cabinet secretaries stumbling away from encounters with Wolfowitz completely baffled, thinking, if not quite in these words, Listen, we all love war crimes here—but this guy is freaking me out.

For some semblance of an understanding of Wolfowitz’s deal, we can start with his childhood. His father, Jacob, lost much of his family in the Holocaust and instilled in his son a keen sense of the perils of non-intervention—of standing idly by, puzzling over logistics, while innocents are slaughtered. This latent strain hardened into ideology at the University of Chicago, where as a graduate student Wolfowitz studied under the conservative political theorist Albert Wohlstetter. Had Wohlstetter had his way there wouldn’t have been an Iraq War, because the world would have ended many decades earlier. He was among the most prominent critics of nuclear detente and a vocal advocate of preventive warfare. (Also, relatedly, a model for Dr. Strangelove.) Wolfowitz was one of a handful of Wohlstetter disciples to lobby for the master’s ideas through multiple Presidential administrations, where they were generally received as strategically unsound if not outright suicidal. And then the towers fell.

The Saddam thing specifically is harder to parse. Mainstream commentators tiptoed around the Israel connection in the months before the war, nervously appending disclaimers about anti-semitism and conspiratorial thinking, but we’re past that point now: it absolutely played a role. Wolfowitz thought Israel was great—he loved it and wanted to help it. Not that there weren’t other explanations. Wolfowitz was—according to Wolfowitz—anguished over the casualties that followed the US' decision not to back the Shia uprising after Operation Desert Storm. He was, we know, swayed by ties to a number of influential Iraqi exiles, among them the ultra-charlatan Ahmed Chalabi. He was the de facto figurehead of the neocons, who had spent a decade constructing an alternate reality in which toppling Saddam was the only thing standing between the US and total annihilation.

Maybe all that is enough. It somehow doesn’t feel like it. Wolfowitz was, is, an ideologue, a fanatic, but the relentlessness with which he pursued his campaign—”the Wolfowitzian fever dream of invading Iraq,” as the journalist Robert Draper has termed it—seemed eventually detached from any specific policy goal or “humanitarian” outcome, a self-sustaining mania impervious to fact. He was not solely responsible for the invasion but he wanted it more than anyone else. As his contemporaries die tragically peaceful deaths, he lives on as an enigma, a shambling non-entity who rose briefly to prominence, destabilized half the world, and then—after a brief tenure as president of the World Bank, a job he lost after giving a raise to a colleague he was dating—vanished into thinktank obscurity, falling from the first rank of Bush-era villains in the popular consciousness. If he is easy to hate, he is harder to understand. What drove Wolfowitz, at the turn of this century?

***

I’d like to say it was this question that first drew me to Wolfowitz. That it was the yawning blankness of his psychology in the lead-up to the invasion, and not his comical name, that plunged me into a Wolfowitzian fever dream of my own, from which I have yet to fully awaken. But no: it was definitely the name. I’d half-remembered it from childhood but encountered it again about four years ago and felt an authentic shiver of ecstasy. It was like hearing The Velvet Underground for the first time. You’d think Jews would be less inclined to find Jewish names amusing but in my own experience the opposite has been true. Last-ditch assimilation anxiety, maybe. More likely some names are just funnier than others, Jewish or otherwise. And “Wolfowitz,” in this respect, is an all-timer: galumphing, sing-songy, lupinely semitic. I smile whenever I think about it. I think about it all the time.

It was the name, much more than the man—about whom, at first, I knew almost nothing—which compelled me at the peak of the pandemic to, among other Wolfowitz-related activities, track down and interview as many of Wolfowitz’s college roommates as I could find. One of them sent me a limerick he’d once composed (excerpt: What became of that once cheerful Paul/Some youthful cohorts recall/He’s turned into a sword/Of dread and discord/Dripping with blood, oil, and gall). Others filled me in on his private life—the everyday Paul. Did you know that Wolfowitz rode a motorcycle? That when he wasn’t riding a motorcycle, he was driving a 1959 Plymouth with enormous fins, which at least one friend of his painfully envied? What about the fact that at Cornell in the 1960s there was a store called Sam’s Sporting Goods, that this store primarily sold sports apparel but also had a newspaper rack, and that the townie boy who minded this rack believed Wolfowitz to be “a real fuckhead,” because Wolfowitz was always coming in and rifling through the newspapers without ever actually buying one, instead just making a big mess that the boy then had to clean up?

In theory I was gathering this material for a novel-in-stories set in a kind of Wolfowitz multiverse, a world bent entirely around Wolfowitz in which the action proceeded primarily through endless Wolfowitz-related monologues (i.e., “As a college student Wolfowitz was ruthlessly, almost mechanically cheerful, essentially addicted to big friendly smiles…”) and in which sections were headed with titles like “THE ORIGINS OF PAUL WOLFOWITZ'S THEORY OF MILITARY STRENGTH IN A UNIPOLAR WORLD, PART ONE: THE ALBERT WOHLSTETTER YEARS." As far as I’m concerned there’s no shame in writing for the market, in giving the people what they want; I’ll finish the project eventually. For now I will say that my relationship with Wolfowitz would never have attained its present depth had I not come to believe that the man himself—independent of his name—is among the funniest characters to grace the world stage this century. Not broad-strokes funny—not funny like Trump. Trump’s a comedian, he wants you to laugh. Wolfowitz doesn’t think of himself as funny. Wolfowitz thinks of himself as a distinguished foreign policy scholar with a track record of dedicated service at the highest ranks of government and academic life. He thinks that when people see him, they see a serious person. He thinks that he’s sane. And there is, to my mind, no richer comic archetype than the demented straight-man (cf. my own personal funny-art canon: Pale Fire, Donald Antrim’s ‘90s novels, the short-lived Comedy Central show Review). This is the only real conclusion to draw from Wolfowitz’s behavior in the aftermath of 9/11. This man whose whole thing was being smart—the lost-in-thought professor, hair askew, too busy working through dense geopolitical abstractions to brush the crumbs off his suit—was a complete fucking lunatic.

***

Yet there are some who persist in believing that the Wolfowitz we came to know ca. 2003 was not the real Wolfowitz. That Iraq was a miscalculation on the part of an otherwise reputable man. In 2013 Andrew Bacevich published an open letter to Wolfowitz which argued that while “the people said to be smart—the ones with fancy résumés who get their op-eds published in the New York Times and appear on TV—really aren’t,” Wolfowitz was an exception. He believed Wolfowitz to be fundamentally humane—“at most a fellow traveler” among the vulgar, bloodthirsty neocons. The letter concluded with the hope that Wolfowitz would break his silence on the war and "help us learn the lessons of Iraq." But the Wolfowitz who would do such a thing—who would look Chuck Todd in the eyes and say "Chuck: I was wrong”—is long dead. Probably he never existed in the first place. And the living, breathing Wolfowitz has spent the last 20 years doubling down. He is happy to critique the course the war took post-invasion (i.e., the course the war took once Wolfowitz was no longer involved with it). But he has never come close to suggesting that the invasion itself was a mistake. This exchange, from a 2022 interview with ABC News Australia on the occasion of the US' withdrawal from Afghanistan, is representative:

INTERVIEWER: America and its allies, like Australia, were told that the War on Terror was going to make the world safer. It appears now that it didn't make the world safer at all, did it?

WOLFOWITZ: We have no idea what the world would be like today if we hadn't done what we did do. I firmly believe it would have been much worse.

More than once, watching this clip, I have tried to picture Wolfowitz in the minutes after it ends. He shuts the laptop (it’s a Zoom interview). He pours some water from the fridge. Is he in a bad mood? Does what has just transpired perturb him? I believe, sincerely, it does not. Whatever set of deformities drove him to orchestrate the invasion in the first place appear to have permanently insulated him from any guilt over what it unleashed. At least Bush has his weird, psychologically crude maimed-veteran paintings: Wolfowitz just seems to genuinely not give a shit. He’s irritated, sure—you can see that in the video—but it is the kind of irritation you’d feel if you accidentally broke your friend’s antique lamp, and then the friend kept bringing it up every single time you hung out. Like: Really? We’re still talking about the lamp? It takes courage and broad-mindedness to recognize that people see you as a world-historical agent of senseless destruction and pain—to recognize that you are, in actual fact, a world-historical agent of senseless destruction and pain—and those are two qualities I suspect Wolfowitz lacks. Already, I imagine, his mood is improving. In his kitchen, in the shadow of 500,000 dead, he pops a couple of cashews, checks his phone. He is a man of substance. He still has work to do.

Daniel Kolitz is a writer in Brooklyn.

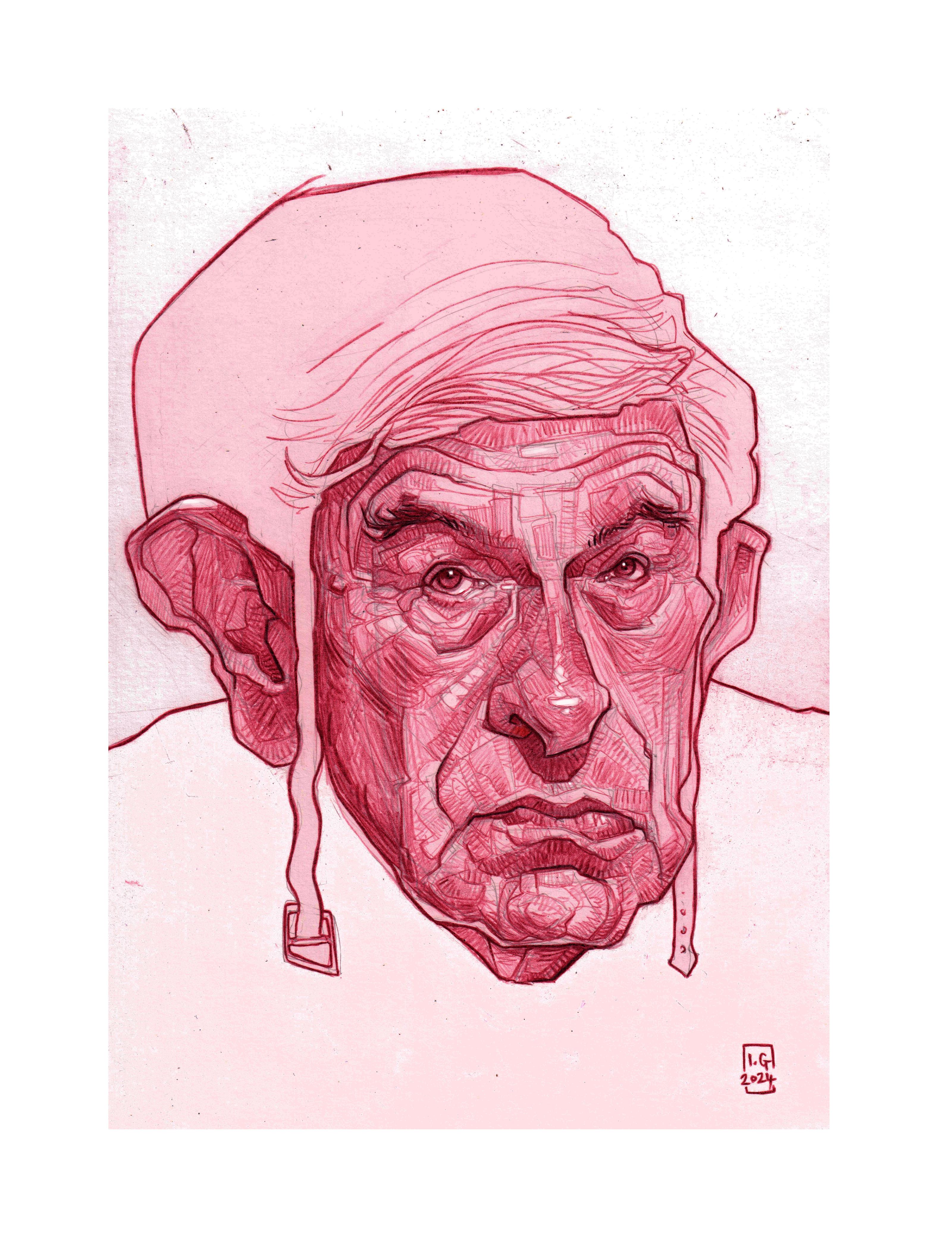

Art by Iddo Goldfarb