Few phenomena in contemporary American life offer a more reliably compelling narrative blueprint than the high school prom. Its rituals and totems have become so neatly packaged that it is difficult to distinguish which of them originated in life, which in art. This is largely thanks to Hollywood glamor, though not exclusively. The prom plot offers the same irresistible will-they-or-won’t-they tension as its more distinguished older sister, the marriage plot, but with a manifest structural advantage. By resolving in coupling without resorting to marriage itself, the prom plot delivers on perhaps the most satisfying catharsis in the Western literary tradition sans its customary sacrifice: possibility. Prom is akin to the dress-rehearsal for a particularly fascinating play, which is probably not a bad metaphor for adolescence overall.

It is in the context of not only American Pie and She’s All That and Ten Things I Hate About You, but also the films that deliberately subvert such entrenched narrative expectations—Mean Girls, even Carrie—that I’ve been lured into analysis of a more personal kind. Satire, parody, horror: all still rely, fundamentally, on the original blueprint. But I can’t find Artie in any of it. His conspicuous absence and the failure of my mental models, my usual cultural touchstones crumbling to dust—this is why, more than 20 years later, my mind still comes to rest on Artie, and the weekend we spent together in New York City, in lieu of his senior prom.

Arthur “Artie” East Irving—not his real name, but close enough—was the kind of boy I categorically should have been attracted to and categorically wasn’t. He was tall and blond and on the first boat of the crew team (most of my boyfriends, both real and imagined, were on the first boat of the crew team). He’d go on to Harvard, albeit with the boost of a postgrad year at an even fancier boarding school in England. Last I’d heard, he’d gotten married and was working at a well-funded tech startup.

My ambivalence was at least partially tautological, adolescents being especially inclined to mistake demand for value, to want what their friends want for no reason beyond their friends’ wanting. Somehow, Artie was never picked up by the recursive algorithm of mimetic desire. But for me, there was another more concrete reason. Aside from my roommates, for whom the school had formally provided addresses and telephone numbers for mini-fridge-coordination purposes, Artie was the only other student whose name I knew on arrival. He was a year older than me, but our fathers had been in the same one, having first met nearly half a century earlier when they’d welcomed the class of 1957.

I should probably pause here and explain that even before I launched my frankly relentless campaign to go to my father’s boarding school, my interest in it bordered on obsession. His nostalgia for the place pervaded our house like second-hand smoke, and even before taking a puff I was addicted irredeemably. The narrative had this American Dream quality: he’d arrived the son of an impoverished Russian immigrant and left with a scholarship to Princeton. Such achievements were always couched as strictly intellectual—their chief benefit being that he hadn’t had to become an investment banker or something, but a tenured English professor.

That my father had been genuinely dazzled more by knowledge than wealth was something I both deeply admired and could not emulate. I was no more fascinated by Ethan Irving than any of the other vested boys in the 1957 yearbook, but I was fascinated by him in the sense that I was fascinated by them all. I can picture Ethan’s senior yearbook photo clearly—like his son, tall and blonde and oar-toting. He and my father hadn’t been particularly close, but had stayed in touch over the years nonetheless. The school had been a different place in the 1950s, before the hard-and-fast sunset of corporal punishment, let alone co-education, and they bore that grizzled, nostalgic kinship of formative shared experience I generally associate with movies set in Vietnam. The discovery that their belated children would likewise be schoolmates was certainly enough to make plans to meet up when they dropped us off in the fall of 2000.

I remember the heady anticipation of our introductions, though it was Ethan, not Artie, who made the stronger first impression. The second or third thing out of his mouth was some comment about my appearance that contemporaneously registered as borderline. Like, Jesus, she’s a knockout. I was fourteen. It both thrilled and horrified me, being adolescently self-conscious and desperate for any kind of flattery, but also instinctively repulsed by him. My mind couldn’t square the attractive young man from my father’s yearbook with the ostentatious gut spilling over his pink shorts. Still, there was something about him that made me relieved to have his approval. In retrospect: the air of money, mixed with that prickly male confidence I’ve come to associate with late-night comedians of this era addressing troubled ingenues. I felt sullied by him and like I’d passed the first, unofficial test of my new world.

Artie himself was quiet. I’m sure he shook my father’s hand, said that it was nice to meet me. His resting face seemed to be one of judgment, and I worried it was as clear to him as it was to me that we were different kinds of legacies. I, too, was there on heavy financial aid. My fashion choices that day had been inspired by The Official Preppy Handbook without a trace of irony, and in my effort to show I belonged, I’d hideously overcompensated—pleated skirt, knee-high socks. I began to doubt myself as Artie’s eyes bore into me, fretting that this staid, haughty boy had the unique potential to disrupt my chance at reinvention. But once our parents left we barely acknowledged each other, and I swiftly made other friends—more swiftly, I believed, than Artie. Whether or not it was true, I soon appraised my social position to be a cut above his, and his presence worried me less. Still, there was always something unsettling about him, this persistent feeling he could see through me, that his isolation was the byproduct not of an inability to socialize so much as the sense he was above doing so—a calm assurance in his inherent superiority, signified precisely by its understatement.

I have few concrete memories of Artie from the ensuing three years; what lingers most is simply that I had a vague extra-awareness of him and avoided his family on parents’ weekends. Then, seemingly out of nowhere, Artie asked me to the senior prom.

I can still see the brick enclave framing his blue blazer, the forthright, almost cavalierness of his question. In forgoing any prologue, he’d stunned me, and my instability in the throes of surprise seemed to somehow favor him. It didn’t matter that I theoretically held the upper hand. Even in seeking my approval, Artie had the power to rile my insecurities. I wondered if his father had put him up to it. And for what reason? As a charity case, or a pretty ornament? I imagined Ethan with a photograph of us on his desk, his gaze on our flushed cheeks and formalwear—and demanded an explanation. Artie knew I was a good student; he wanted to go with someone who could hold an actual conversation. While I bristled at the implication most girls couldn’t, this answer sufficed, and I accepted Artie’s invitation. I wondered if he might be gay, but there was also something in his coolness and pride that recalled Mr. Darcy—and I considered, too, if his demeanor might suggest some fiery passion of the decorous that, while unrequited, was nonetheless complimentary.

I have no memory of the logistics, whether it was Artie or my mother or father who told me the change of plan. Artie didn’t, it turned out, actually want to go to the prom. He wanted to take me to New York for the weekend, to a fancy French restaurant instead of the dance. We would stay at his parents’ apartment, which concerned me at first, the idea of being in such close proximity to his father, until I learned only his mother, Marian, would be home. I was to have my own room, of course: his sister’s. She was away at college, at Smith or Wesleyan or something.

It was the sort of proposal I think my parents would have been inclined to mistrust if it had been any other boy. But it was Artie, and their approval was never in question. I considered making some excuse of my own, but was just self-aware enough to understand the transparently unflattering motivations this would impart on me. It’s not like I was devoid of empathy and character, either. I’d given Artie my word, and felt a genuine moral obligation to swallow my disappointment. Plus, my mother said I could still get the expensive strapless black gown I’d tried on in Litchfield a few weekends earlier—and there’d still be the afterparty in the City.

The Irvings’ apartment appeared unremarkable to me at the time. It was about the same size as the house I’d grown up in and decorated similarly: antique furniture, lots of books, a few good paintings, outdated bathrooms. I knew New York was “more expensive” than central Pennsylvania, but was clueless as to the magnitude of this disparity. In retrospect, it was a multi-million dollar apartment: three bedrooms on the Upper East Side, with the sort of stately, sweeping views that Sex and the City had convinced me were commonplace.

It was late by the time we arrived on Friday. Marian Irving—the kind of tall, imposing woman you’d call “statuesque”—was welcoming, if scarce, showing me to Artie’s sister’s room, hanging up my dress. She’d ordered Chinese; it was in the fridge. We were alone for the rest of the evening, and there was something extra-intimate about it: quiet, dimly lit. A dress rehearsal of evenings I’d spend in the City years later, reheating takeout with my husband. I want to say I was reminded of these future evenings even then, as I stood in Artie’s parents’ kitchen, unable to see the face of the person they’d someday be shared with, but with an eerie premonition they would come. It was embarrassing, having such thoughts in Artie’s presence, acting so grown up together—as if by using the microwave I was implicitly extending a premature domestic invitation to him. But perhaps this is just the crux of why it’s so hard to be an adolescent, why the dress-rehearsal metaphor works so well: the perpetual cognitive dissonance between acting like an adult already and the utter terror of becoming one.

Artie vacillated between fastidious politeness and making off-kilter jokes that seemed both explicitly designed to test my poise and a cover for his own discomfort. While he still gave me the disquieting sense of being carefully observed, this was newly offset by my impression he too was self-conscious—aware that I was carefully observing him. There wasn’t sexual tension, exactly, but something closer to the tension of whether or not there would be—and I think we were both relieved when it came time to adjourn to our rooms. I slept horribly, my brain alight with the specter of his proximity, the fear I’d make too much noise if I had to use the bathroom. The anxiety of being unable to sleep itself.

Marian was alone at the dining table when I emerged the next morning, reading the paper over breakfast in a manner so WASPy and old fashioned that the memory blurs in my mind with fictional scenes from Mad Men.

—I’ve heard you’re interested in art, Natasha, she said without preface.

Who had told her this? It was such a decorous, almost formal statement, and yet the ease with which she said it, standing up and pouring me an orange juice, struck me as alarmingly familiar. She seemed impossibly relaxed in her surroundings despite my presence, like she hadn’t made any special preparations or adjustments on my account. This isn’t to say she was unaccomodating, but that it was the sort of intimate posture a genteel woman might take around a well-liked in-law.

—Yes, I said pleasantly, making eye contact, determined to mirror her confidence.

—Artie wants to take you to the Guggenheim today, to see the Barney installation.

—That’d be great, I said, without the slightest idea who Barney was.

Marian nodded approvingly. She didn’t say anything twee or embarrassing, the way parents of teenagers often feel compelled to do, but the wry look she gave me nevertheless seemed to lend uncomfortable credence to my Mr. Darcy theory, and when Artie entered the room, freshly dressed and showered, we both blushed furiously.

The plan, it turned out, was to meet up with two other boys from school and all head to the Guggenheim together. Fred Shultz and Dean Reynolds III were the sort of boys who’d always given me Rosencrantz and Guildenstern vibes, minor characters in the periphery of my social consciousness, but I was grateful for their diffusive presence. This gratitude grew substantially once we got to the museum, and I learned what the “Barney installation” actually was. I’m not sure what I was expecting to see at the Guggenheim that day, garnering the sophisticated approval of Marian Irving—but I can guarantee you it wasn’t the Cremaster cycle.

The Guggenheim’s website opens its description of the Cremaster cycle as “a self-enclosed aesthetic system consisting of five feature-length films that explore processes of creation,” but it’s basically an epic tribute to balls. (The Guggenheim: “Its conceptual departure point is the male cremaster muscle, which controls testicular contractions in response to external stimuli.”) Its level of weirdness threatens the plausible extremity of the word. The films, which were shot out of order from 1994 to 2002, are almost entirely devoid of plot, let alone an archetypal one—but, say, exhaustively follow Matthew Barney as a ginger fawn crawling up an enormous, Vaseline-coated anus (Cremaster 4), or as a maypole-dicked merman hounded by pigeons (Cremaster 5). Cremaster 3, the cycle’s apex, features Barney scaling the walls of the Guggenheim in a kilt and fuzzy, scrotal hat, foreshadowing the fusion of film and set in the exhibition. A bloody cloth hangs out of his mouth in a way that seems nearly anatomical, for an overall effect falling somewhere between Mel Gibson in Braveheart and Dr. Zoidberg, the pink, proboscidal character on Futurama. The portraits of Barney in this getup are some of the most famous in the cycle, perhaps because they are—if you can believe it—some of the least disturbing. The merman costume I mentioned in Cremaster 5 reminds me of a live-action remake of the South Park episode where Kyle’s dad gets disastrous plastic surgery to look like a dolphin. In another scene from Cremaster 3, Barney is subjected to medieval dental work in the nude while taking a prolapsed intestinal shit. I still shudder when I picture it.

You can imagine how four unsupervised teenagers reacted. For all its esoteric sophistication, the Cremaster cycle is almost less conducive to maturity than American Pie. Even now, revisiting it as an adult who has worked in museums, who generally likes pretentious things and is predisposed to defend phrases like “self-enclosed aesthetic system”—who has written a novel about snobs and art—my visceral reaction is: what the fuck. It is a testament to the sheer magnitude of what a megalomaniacal white dude with an Ivy League degree can get away with. In spite of our snickering eye rolls, we were all transfixed, reveling in every new absurdity as we worked to outdo one another’s scatological puns.

One might have predicted I’d be awkwardly left out in such an environment, the only girl with three boys—but they included me collegially. I mentally upgraded Dean from “occasionally amusing” to “hilarious” and reflected that Fred, too, was a significantly more complex individual than I’d ever before given him credit. Still, even as these impressions careened toward admiration, I couldn’t shake the sense Artie had invited them less for cover than relief, and as the afternoon wore on, I found myself increasingly unable to deny his preeminence among them. By the time we left the museum, several hours later, I was still anxious about our dinner, but less due to its situational embarrassment than my prospective appearance for the occasion. I wanted to look achingly ravishing.

Artie wore a slim-cut suit in lieu of a tuxedo, which seemed vaguely disappointing vis-à-vis my narrative expectations but was, of course, the more appropriate choice for the occasion. He’d gotten me a tasteful corsage: white roses, for contrast with my dress. Even in his mother’s presence, he admired my appearance with the forthright confidence of a well-adjusted man, and I tried my best to reciprocate. Marian took several photos, and likewise complimented us both generously, but again resisted the sort of embarrassing cooing Amy Poehler so brilliantly parodies. Marian treated us, in other words, like adults; like this was not a rehearsal but opening night, reflecting our own impressions of the situation. She wasn’t going to wait up for us, she said. Enjoy the evening. There was no curfew; it was never even mentioned. Her trust in our judgment was so self-evident she didn’t bother reminding us she trusted it.

It was my first time at the kind of restaurant that doesn’t include prices on women’s menus, a detail I’ve come to systematically note and appreciate for its descriptive efficiency. Our table was in a sparse room with only five or six more, spread far enough apart for other conversations to provide a pleasant humming backdrop as opposed to competition. I noticed the other diners on entry—men and women who reminded me of Artie’s parents, looking at us nostalgically—but not again after I sat down. Every detail of the interior was designed to focus your attention on your immediate socio-culinary experience, as if a spotlight hung over the table, blacking out everything around it. Artie ordered a bottle of wine, and no one carded us. In spite of his marked seriousness, I’d never seen him more at ease, and the conversation flowed as naturally as teenage conversation can. We discussed school, our parents, the Cremaster cycle. The food was excellent, and we ate slowly and deliberately. If the previous night had been eerie in its premonition of actual quotidian adulthood, the restaurant was charming in its idealized version of it. Our dinner out was the paragon of “adulthood” as conceived by privileged adolescents, and, being privileged adolescents, its formality ironically made for a far more relaxed and comfortable environment.

Here is the part of the evening when my memories start to break down. Up to this point I can attest to the broad brushstrokes, to the emotional fidelity. But after dinner, I grow susceptible to the kind of self-preserving revisions I acutely associate with protagonists in Ishiguro novels, and it is only through the most delicate mental excavation that I can remind myself I’m an author and not a character.

If I told you that Artie and I stopped by the afterparty for a while before heading back to his parents’ apartment and falling asleep, this would technically be accurate. For many years, it was what I told myself. In forcing myself to elaborate, I’m still tempted to adjust the lighting—to say I didn’t realize until I was already inside the bar that Artie wasn’t behind me. It’s true it was loud; dark and smoky. But the moment we stood in sight of our peers, I was also no longer looking for him. With the change of setting, I was either awoken or rehypnotized, the spell—or clarity—of our dinner broken. A well-liked senior boy recognized me, pulling me past the bouncer and into the prom plot proper. He offered to buy me a drink. I want to claim I didn’t see Artie through the window, but I did. I wasn’t drunk enough to relegate it to my subconscious forever: the conversation that for 20 years I’ve avoided reliving.

—So wait, why weren’t you at prom? The well-liked senior asked me.

I could feel his eyes on me, and the envious eyes of other girls—girls who I envied. He’d been smoking, and the smell was unpleasant, but the girls’ desire was compelling, the shadows of their off-campus lives in Greenwich and Hong Kong, their closets full of Marc Jacobs and Burberry giving unearned weight to their envy of me. When I’d yearned to be asked to prom, for the black strapless dress, to go to the afterparty—for all the established beats of the prom plot—this envy, its validating power, was ultimately what I’d been seeking. I leaned toward the boy conspiratorially:

—Artie wanted to go to a restaurant instead, just the two of us.

—Oh my god, that’s so creepy, he laughed. Why?

I shrugged nonchalantly, the first pang of guilt roiling inside me.

—No idea, I said.

—Where even is he? Wait, is that him outside? Can he not get in? Ha ha.

I tried to give the impression of looking for Artie without actually making eye contact with him. Still, I could see he was waving to me frantically.

—What a loser, the boy said, more with apathy than malice.

I hope I didn’t agree with him, but I fear that I did. I’m not sure how much longer I stayed at the bar either, willfully ignoring Artie’s physical pleading, caught between my guilt and the overwhelming desire to just enjoy the party with the climactic joie de vivre I was so painstakingly affecting. I pitied Artie, but I pitied myself more. There is a cruel irony to getting what you want and being incapable of reveling in it. I cast furtive glances out the window, and the well-liked senior boy, sensing my ambivalence, turned his attention away from me.

Why did I need either of them? Why did my most sought after narrative arcs so consistently leave me beholden to someone else’s generosity? If the price isn’t listed, you can’t afford it. No woman can. Even though I was the one at the party, with Artie looking in, I envied him. In garnering the well-liked boy’s passing favor, I understood the ischemata behind it: that the shard-like benefits afforded to women on account of their beauty structurally reinforce the power of men, and it is nearly impossible to extract them without getting cut. No amount of elite education or literary critical ability would be able to counter this. Not even the absence of plot could free me from the asymmetries of femininity, from a patriarchal conditioning so all-encompassing I couldn’t help but reinforce it myself, and quite often willingly. The deference afforded to Matthew Barney was categorically foreclosed. That this is true does not constitute an excuse for my behavior with regard to Artie. There is none, and I’m still ashamed of how I treated him. But my behavior also can’t and shouldn’t minimize the structural discrepancy, that our self-enclosed aesthetic system is ultimately in tribute to balls.

I exited the bar sheepishly, prepared for Artie to be furious. His face glowed hot, but as I got closer it became clear this was due less to fury than embarrassment. He was close to tears.

—How could you leave me like that? He demanded, walking in the direction of his parents’ apartment.

—I’m sorry—

—Seriously, what were you thinking? Don’t you realize I’m responsible for you?

—It’s not like you’re my boyfriend!

—I mean because you’re my guest, Natasha! Jesus. What if something bad had happened? Our parents would have killed me.

—I’m sorry! I slurred, trying to keep up with his pace.

—How wasted are you? He slowed down, wrapping his jacket around me. Don’t you know that guy’s a predator? Did he slip something into your drink? Are you ok? Do you need anything?

—Um, could I have a bagel . . . please?

He made me one back at the apartment: toasted, with cream cheese. We sat on the floor of the kitchen together while I ate it, silent in our respective humiliation. Artie’s eyes were downcast; mine were pleading.

—I’m sorry, I said again, meaning it this time.

He made eye contact.

—It’s okay.

— . . .

—We should probably go to bed.

I stood up, handing him the empty plate, and Artie put it in the dishwasher. I started down the hall but stopped at the door to his sister’s room.

—Artie? I turned back toward him.

—Yes?

—Thank you for dinner.

He stood there for a moment, looking at me. I was afraid—a little of him, a lot of my own uncertainty—but when he bent forward, his lips touched only the lightest kiss to my cheek.

—It was my pleasure, Artie said softly, and walked down the hall to his room.

A. Natasha Joukovsky is the author of the novel The Portrait of a Mirror and a “quite useless” newsletter. She lives in Washington, D.C.

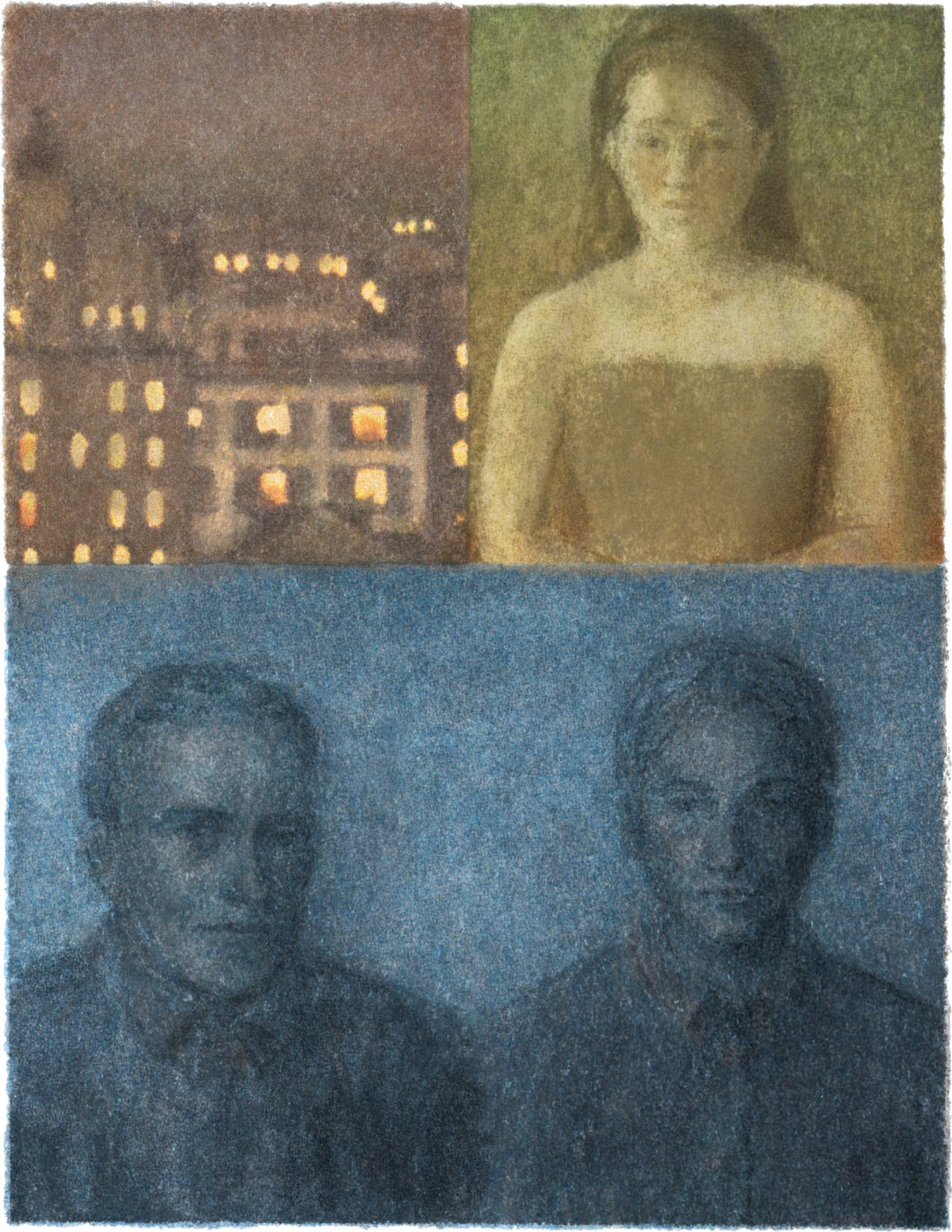

Art by Calli Ryan