Ted Turner hated the news. He found it dull, depressing and, above all else, bad for morale. If you asked him—or even if you didn’t—he’d tell you that just about everything wrong with America could be blamed on the news. “As a proud patriot, he felt TV news had poisoned the populace against the military by portraying the war in Vietnam as an unnecessary disgrace,” writes Lisa Napoli in Up All Night: Ted Turner, CNN, and the Birth of 24-Hour News. Yet Turner, with the founding of CNN in 1980, changed the very nature of broadcast journalism, perhaps more than any other individual before or since.

When this story gets told, it’s often presented as an irony. Good ol’ Ted, the populist tycoon, the Mouth of the South himself, turning on a dime and getting respectable. Yet it’s better understood as a prophecy. If the news was what ailed America, then dadgummit, Ted was going to create a cure. A man of boundless ego, charisma and charm, Turner took it upon himself to save the world through television. Salvation may be debatable, yet it’s undeniable that he changed the medium, and the world along with it. But the world he tried to save left him behind.

***

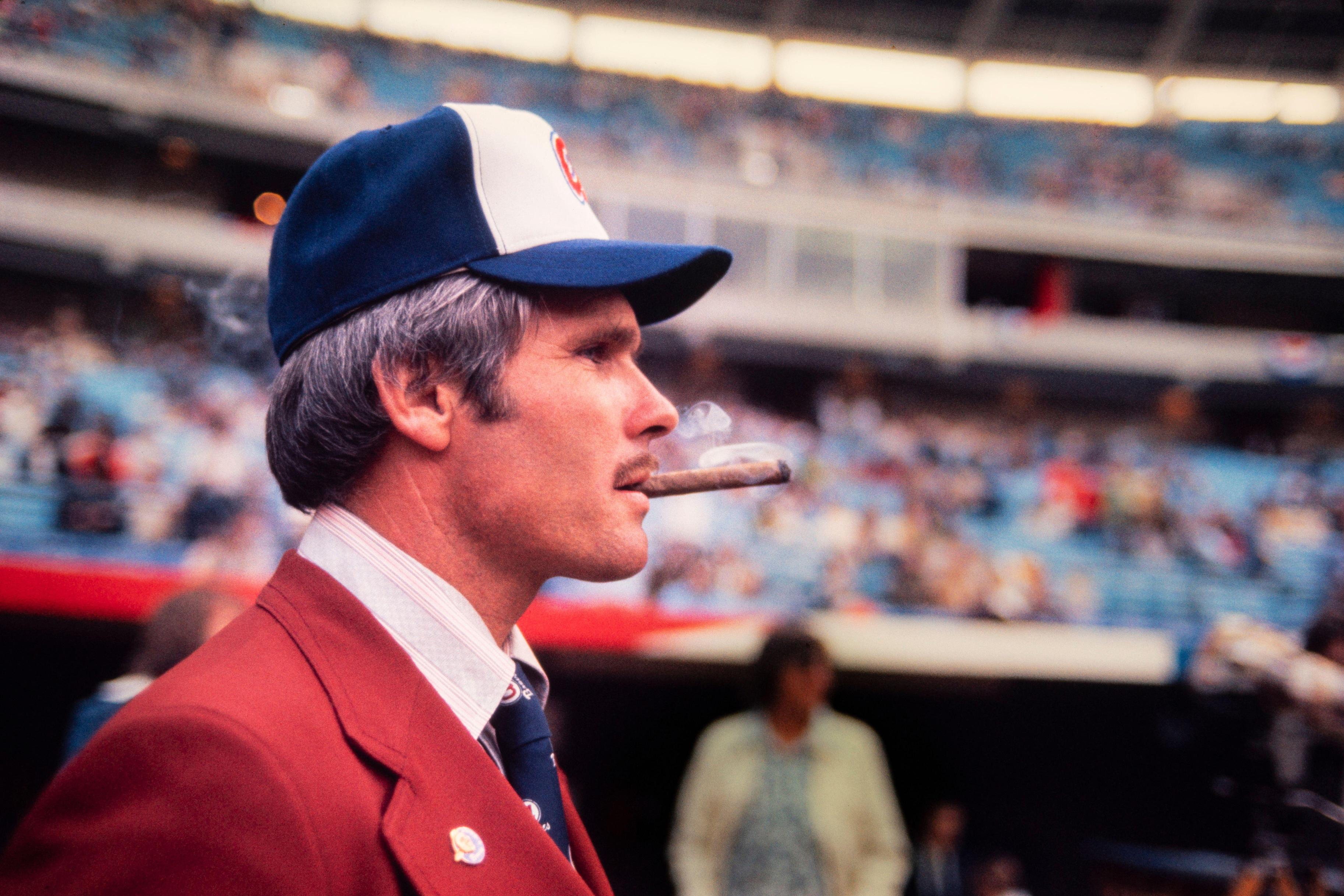

Turner was born in 1938. His father founded and ran a company called Turner Outdoor, which specialized in billboards throughout the South. Turner took over the business in 1963, when he was only 24 years old, following his father’s suicide. Turner was devastated, yet he didn’t pause to grieve. Instead, he worked harder than ever. After plastering the region with billboards, Turner turned to the airwaves. In 1970, he bought a local television station in Atlanta and named it WTCG, though it would become known to its many fans in the region as Channel 17. Channel 17 specialized in populist, crowd-pleasing fare: reruns of I Love Lucy and The Andy Griffith Show, professional wrestling, Atlanta Braves baseball games. Ratings were strong, which brought in advertising revenue. Turner used the money to buy the Braves outright so he could air all their games on Channel 17, giving him hours and hours of much-needed programming. He didn’t want any news at all—too depressing—but federal regulations stipulated that a certain amount of daily programming had to be educational and informative. Turner assented by airing, late at night, a jokey newscast that resembled Saturday Night Live more than Walter Cronkite.

But Turner wanted more. He fashioned himself a modern Alexander the Great, his favorite figure from his undergraduate years studying classics. He wanted to show those New York snobs in media that he could beat them at their own game. And that game was news. Turner came to see this at a broadcasters’ conference, where he met a disgruntled member of that very New York media class, an editor and producer named Reese Schonfeld. A Jew from Newark, New Jersey, Schonfeld had worked his way up the media industry without quite reaching the top. He wanted to democratize the news, to free it from the tidy packages of the evening broadcast, and give it to the people. Schonfeld and Turner didn’t hit it off, exactly. They were different men from different backgrounds: Turner the gregarious Southern charmer, Schonfeld the East Coast inside-outsider. But they recognized in each other a means to achieve their goals. Changing the news, for Schonfeld; growing his media empire, for Turner.

Their baby, Cable News Network, went live on June 1, 1980. At first, the novelty of CNN seemed like just that. The news, all day, even when there wasn’t much going on. “Junk food news,” critics called it. Then came an event that allowed CNN to demonstrate its strengths—and to change the very tense of broadcasting.

On March 30, 1981, shots rang out at the Hilton Hotel in Washington, DC. CNN’s on-air correspondents responded to it in real time, piecing together events from wire and reports and simple deduction, before arriving at the story: an attempt had been made on President Ronald Reagan’s life. Details were few, sometimes even contradictory, but CNN stayed live, piecing things together. Minutes later—a lifetime in broadcasting—the major news networks chimed in with the stories, eventually confirming that Reagan was unharmed, and that James Baker, his press secretary, had been wounded. The definition of news was changed, “as something that is happening rather than something that has happened,” writes Porter Bibb in his biography of Turner, It Ain’t as Easy as It Looks.

***

The 1980s were a good decade for Turner. CNN continued to rise, redefining the nature of broadcast journalism. His overall media empire grew, as well. In 1985, he purchased MGM, the movie studio. He got a nice price for it, too, as it was on the verge of financial collapse. The studio’s massive library of classic films enabled Turner to create TNT, which would go on to become an even more successful channel than TBS, as WTCG was eventually named. Cartoon Network came along soon enough, as well as TCM. The Turner name was everywhere on the cable dial.

Yet Turner, as he became more influential and saw more of the world, grew increasingly worried over its fate. Nuclear weapons lay in stockpiles, with Armageddon just the push of a button away. The destruction of the environment continued apace, with no relief in sight. Once a flag-waving conservative, worried that the nightly news would discourage our boys overseas, Turner threw himself into self-described “bleeding heart” philanthropic causes, giving speeches at the UN, starting the Goodwill Games (at huge personal financial cost) to promote international peace. Most familiar to millennials, he helped create Captain Planet, an endearingly earnest cartoon where a cast of multicultural teens worked with the titular superhero to stop villains from polluting the rainforest. Yet his sense of worry did not abate.

Nineteen-ninety-one saw the pinnacle of Turner’s achievements, both professionally and personally. The Gulf War in Iraq was covered exhaustively by CNN, landing the network its highest ratings ever. “CNN used to be called the little network that could. They are no longer little,” said Tom Brokaw, anchor of the NBC evening news. Others were less complimentary. French theorist Jean Baudrillard, perhaps best known for inspiring The Matrix, wrote a book titled The Gulf War Did Not Take Place, arguing that the conflict was a “virtual war,” staged for the benefit of the cameras. Virtual or not, it landed Turner on the cover of Time magazine as Man of the Year.

Turner also made news with his personal life. In December of that year, he married Jane Fonda. Instantly, they became a world-bestriding power couple, merging the entertainment and journalism worlds with startling intimacy. A restless man who hated to be alone, Turner found in Fonda an equal, one who wouldn’t put up with being ignored, which he had done with many of his earlier relationships. Turner himself calmed down too, spending more time with family members, especially his children from earlier marriages. For a man who knew difficulty from a young age—a demanding father who eventually committed suicide—this was arguably the happiest period of Turner’s life.

Yet the decade also saw the beginning of his decline, when the future would eclipse him.

***

When he was wheeling and dealing in the ‘80s, Turner made a decision that would haunt him. Eager to grow his empire, he sold a major stake in his company to Time Warner, perhaps the most prestigious name in media at the time. The deal gave him even more access to some of the best programming available—but it also gave Time Warner access to his own business. This all came to a head in 2000, during what Ken Auletta, in his book Media Man, describes as “The Merger from Hell.”

The internet was exploding during the mid-to-late ‘90s, and the biggest company in the business was America Online. AOL added millions of new users to its internet service every year, convincing many that it was on track to become the AT&T of the internet. The company was valued incredibly highly, and it leveraged that value to purchase Time Warner and merge the two companies into one media behemoth. AOL would own distribution, the thinking went, while Time Warner, with its vast archives, would handle the content side, giving those internet users new things to watch and read.

Yet the rollout was disastrous. Becoming a behemoth, it turns out, makes it difficult to navigate new challenges, which only came along at a faster clip in the 21st century. Executives fought in boardrooms and badmouthed each other behind their backs. And Turner, accustomed to being the loudest voice no matter the room, found himself getting shut out. There were enough bosses already at AOL Time Warner. Add Turner to the mix, and nothing would get done.

Turner spent a few years in corporate limbo. As AOL Time Warner failed to deliver on its promises, Turner saw his own fortune, which was tied up in company stock, nosedive. His personal life fared no better: his marriage to Fonda ended in 2000, and he was lonelier than ever. Frustrated and tired, Turner resigned from the AOL Time Warner board in 2003, stunning the business media. This Alexander the Great may have conquered the media world, but then that world changed. As television waned, and the Internet 2.0 of Google and Facebook arose, Turner was left behind.

At the time of this writing, Turner is 85. He divides his time among his many properties, from his Montana ranch to his Florida estate. He is still involved in philanthropic work, as concerned as ever about the fate of the planet. But he is longer the captain, just a passenger.

Adam Fleming Petty is the author of the novella Followers. His work has appeared in The Washington Post, The Atlantic, Commonweal, and many other venues. He lives in Michigan.